The symbolism is recognizable, but as what depends on the eventual outcome. Dateline April 5, 2015, Easter Sunday, “Rolling Stone and UVA: The Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism Report” posted to the magazine’s website. The holiday celebrates Jesus Christ’s resurrection, following crucifixion. The Washington Post and several other organizations crucified Rolling Stone in December 2014 for long-form news story “A Rape on Campus”. The exhaustive autopsy of the story’s reporting and publication is another another crucifixion, arriving on a day that celebrates resurrection, salvation. Will RS have the one by voluntarily inviting the other?

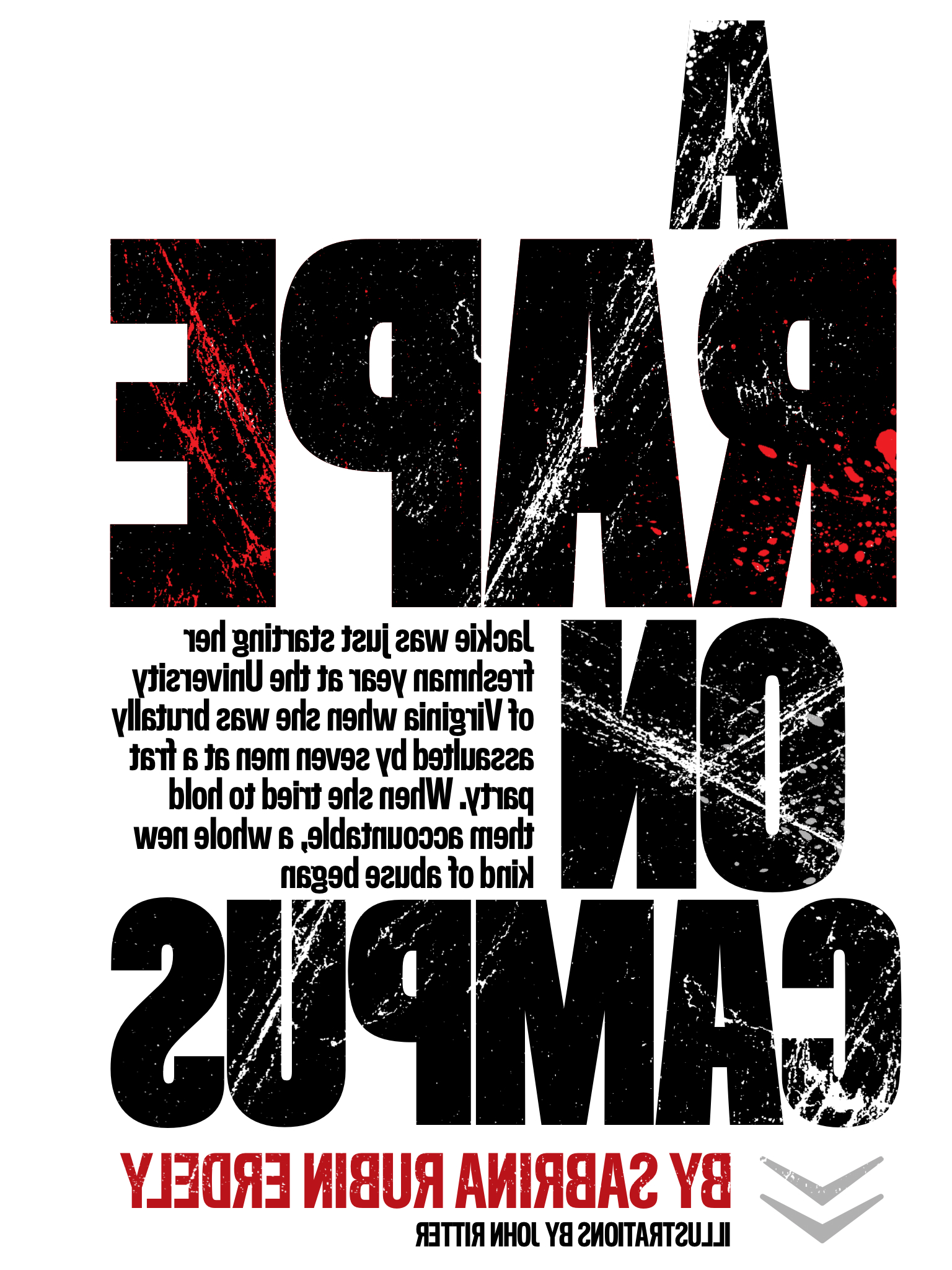

“A Rape on Campus” spotlights the alleged sexual assault of a University of Virginia student identified as Jackie. The investigative report paints a campus culture of acceptable assault without reproach or reprisal. But the veracity of Jackie’s account later collapsed. Rolling Stone sought outside examination, which by itself demonstrates just how strongly the magazine strives to report responsibly.

“We reached out to Steve Coll, dean of the Columbia School of Journalism, and a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter himself, who accepted our offer”, RS managing editor Will Dana writes in the introduction. Dean Coll shares the byline with Sheila Coronel and Derek Kravitz.

The forensic analysis is one of the most-important pieces of journalism you will ever read. The original RS story and this post-mortem should be required reading by all news gatherers and must be made part of the curriculum of all journalism schools. The voluntary look inside the magazine’s editorial practices and processes is unprecedented and commendable. Vultures will circle demanding Rolling Stone resignations so their editorials can feast a competitor’s carcass. Shame on them! RS editors should be praised for laying their sins before readers and everyone else.

With publication of the CSJ analysis, “we are officially retracting ‘A Rape on Campus'”, Will Dana acknowledges, while promising editorial changes based on the journalism school’s recommendations.

A less-responsible ME or publication would do no such thing—or invite outside scrutiny—that spotlights something many people already have forgotten. Journalism is supposed to be a sacred trust working for the public interest. It’s not really in Rolling Stone‘s self-interest to draw more attention to a story vilified by competitors and other accusers. Reopening this drama very much serves the public good, for many reasons, however. Among the most important: Correcting a record that may make future rape victims less likely to step forward.

Crisis of Faith

During the news media melee and second-guessing, in mid-December, I defended Rolling Stone in a long missive that questioned critics’ motivations. Today, I seriously considered unpublishing my 4,300-word analysis in context of the RS retraction. Because what defense is there? But my rebuttal focused on the sloppy reporting of others trying to gut Rolling Stone, while observing clear evidence the magazine corroborated and fact-checked. So I will let my December post stand. (By contrast, Rolling Stone sends the original “A Rape on Campus” link to the CJS forensic analysis, which I see as a mistake.)

Washington Post largely led the assault against Rolling Stone, which on Dec. 5, 2014 issued what effectively is an apology but not a retraction. I criticized, contending that “editors were wrong to issue an apology based on reporting conducted by the Washington Post. The magazine should have independently followed up and issued the statement, if any, based solely on in-house reporting”. My mistake. Turns out that Rolling Stone acted based on concerns raised by the story’s writer, Sabrina Rubin Erdely.

Jackie had refused to give the name of the student, a lifeguard she had worked with, who invited her to the fraternity and played a crucial role in the alleged gang rape. Following the story’s publication, Sabrina Rubin Erdely finally convinced the alleged victim to disclose the name. According to CSJ investigators:

But as the reporter typed, her fingers stopped. Jackie was unsure how to spell the lifeguard’s last name. Jackie speculated aloud about possible variations. ‘An alarm bell went off in my head’, Erdely said. How could Jackie not know the exact name of someone she said had carried out such a terrible crime against her—a man she professed to fear deeply?

Context is necessary. Jackie’s account of the alleged rape was otherwise quite detailed as given to the RS writer and later to fact-checkers. Dean Coll and contributors’ explain:

Over the next few days, worried about the integrity of her story, the reporter investigated the name Jackie had provided, but she was unable to confirm that he worked at the pool, was a member of the fraternity Jackie had identified, or had other connections to Jackie or her description of her assault. She discussed her concerns with her editors…Late on Dec. 4, Jackie texted Erdely, and the writer called back. It was by now after midnight. ‘We proceeded to have a conversation that led me to have serious doubts’, Erdely said.

She telephoned her principal editor on the story, Sean Woods, and said she had now lost confidence in the accuracy of her published description of Jackie’s assault. Woods, who had been an editor at Rolling Stone since 2004, ‘was just stunned’, he said. He ‘raced into the office’ to help decide what to do next.

The magazine issued the apology, expressing grave concerns about Jackie’s account without yet retracting the story. The key points that I take away and you should, too:

- Erdely followed up her reporting and revealed doubts to her editors.

- By issuing the statement, editors rightly responded to the reporters’ doubts rather than (solely) to outside critics.

- When confronted with questions about the story’s truthfulness, editors acted responsibly by exposing the bitter truth to their readers.

The Betrayl

“Rolling Stone‘s repudiation of the main narrative in ‘A Rape on Campus’ is a story of journalistic failure that was avoidable”, CSJ investigators find. “The failure encompassed reporting, editing, editorial supervision, and fact-checking. The magazine set aside or rationalized as unnecessary essential practices of reporting that, if pursued, would likely have led the magazine’s editors to reconsider publishing Jackie’s narrative so prominently, if at all”.

Before continuing, something needs clarification. The magazine gave Dean Coll and his compatriots full access, which includes Sabrina Rubin Erdely’s reporting notes. The forensic analysis reveals cautious editorial culture and fact-checking. For example, a Rolling Stone fact-checker “spent more than four hours on the telephone with Jackie, reviewing every detail of her experience”.

The point: The autopsy does not reveal that Rolling Stone runs a caviler newsroom. Like many pre-Internet magazines, stories are scrutinized at different editorial levels, which includes the fact-checker.

By contrast, I see too much irresponsible reporting every day, where blogs are used as original sources to propagate rumors and, ultimately, misinformation. The editorial process is post first for pageviews, don’t ask questions later. Fact checking amounts to little more than ensuring the writer left nothing behind during the copy-paste process from the sourced blog. By comparison, Rolling Stone operates with fairly strict editorial ethics and practices—and still failed. The lessons should apply to all.

The major editorial participants in this drama largely blame their deference to Jackie, protecting her anonymity and retaining her as a source, as the point of failure. But the CSJ investigators disagree, observing problems in methodology that are all the more disturbing because processes were in place: “The editors made judgments about attribution, fact-checking, and verification that greatly increased their risks of error but had little or nothing to do with protecting Jackie’s position”.

In my work as a journalist, I have several steadfast rules:

- Ask “Who benefits?’

- Follow the reporting

- Use original sources

- Assume that everyone lies

- Write what you know to be true

I call these out, because in my reading the CSJ analysis twice, the major point of failure I see is the reporting. Sabrina Rubin Erdely relied too much on Jackie’s account, including what the friends who counseled her said. Meanwhile, the writer didn’t follow all the leads to obtain crucial information that might have changed the story’s direction. Jackie’s story should have been challenged more, by uncovering additional corroborating sources.

Three Witnesses

Jackie said that three friends helped her following the alleged gang rape; one named Ryan. She claimed that they counseled her not to report the crime, which fit nicely into a larger narrative about a campus culture overly tolerant of sexual abuse.

“The scene she painted for Rolling Stone‘s writer was unflattering to all three former friends” the CSJ investigators observe. “Journalistic practice—and basic fairness—require that if a reporter intends to publish derogatory information about anyone, he or she should seek that person’s side of the story”. While making some effort to identify the three, for which the alleged victim gave first names, “instead, Erdely relied on Jackie” as primary source.

But following the story’s publication, Ryan was identified and disputed some things that Jackie said about their communications. From the forensic analysis: “If Erdely had learned Ryan’s account that Jackie had fabricated their conversation, she would have changed course immediately, to research other UVA rape cases free of such contradictions, she said later”.

Editor Sam Woods oversaw the story and missed opportunity to pushback about contacting the three friends, whose statements are crucial, Dean Coll and the other contributors conclude. In reading the post-mortem, I am reminded of airplane crashes, where a cascade of failures usually are cause but where one thing or action could have changed everything. The investigators write:

In hindsight, the most consequential decision Rolling Stone made was to accept that Erdely had not contacted the three friends who spoke with Jackie on the night she said she was raped. That was the reporting path, if taken, that would have almost certainly led the magazine’s editors to change plans.

Let’s illuminate what this means. Rolling Stone editors assigned the story. This isn’t an instance of the writer uncovering a shocking rape victim and making a pitch. As such, Jackie’s account, while the framework, isn’t necessary. Erdely could have found another victim. The investigative report isn’t predicated on Jackie. But the unraveling of her account undoes all the other legitimate reporting therein. In my reading, much of the non-Jackie material stands on its merits but, particularly in context of the official retraction, is nevertheless discredited, too.

Related is the alleged victim’s discredited credibility, and what it represents. “Rolling Stone‘s retraction of its reporting about Jackie concerned the story it printed”, the CSJ investigators conclude. “The retraction cannot be understood as evidence about what actually happened to Jackie on the night of Sept. 28, 2012. If Jackie was attacked and, if so, by whom, cannot be established definitively from the evidence available”.

New Life?

Sabrina Rubin Erdely spent six months working on a story now disavowed. “A Rape on Campus” will be gang-banged, yet again, over the coming days as she, the magazine, and its editors once more are ravaged by their media peers.

The irony is thick, because so many of the accusers are guilty of much worse. Online journalism is a madhouse of thinly-sourced stories masquerading as much more. By contrast, Rolling Stone‘s sin is good intentions gone bad.

If you closely examine the reporting process the investigators call out and match it against “A Rape on Campus”, Sabrina Rubin Erdely clearly was thorough in her reporting and sourcing. She just wasn’t thorough enough. I see no deception, and the CSJ forensic analysis finds none, either: “There is no evidence in Erdely’s materials or from interviews with her subjects that she invented facts; the problem was that she relied on what Jackie told her without vetting its accuracy”.

Rolling Stone editors let this happen, and they will not be easily forgiven by critics guilty of egregious antics but accusing another of much more. That was the pattern in December 2014, and I see no reason why it won’t repeat now.

But there is opportunity here, and I circle back to the symbolism of that Easter Sunday dateline: New life. Resurrection. Rolling Stone must learn from its mistakes and lead, at the least, the journalism elite by example. But the lessons should apply to all news gatherers, and the mistakes should be opportunity for greater discussion about what editorial and reporting processes are the most sensible as the Fourth and Fifth Estates collide.

The Columbia School of Journalism autopsy is a roadmap for better defining sensible editorial, reporting, sourcing, and verification practices. But it is the beginning of a process, not the end of one. “A Campus Rape” is a unique opportunity, since the mistakes are really about methodologies that can be identified and fixed for everyone. That isn’t the case when reporters make up shit, like inventing sources. Isolated incidents of journalist deception aren’t meaningful. Sources lie to everyone, and Jackie’s integrity and reliability is core to understanding what went wrong how to do better.

In closing, I caution Rolling Stone editors not be too cautious. Continue the aggressive investigative reporting that keeps me a subscriber (recently gone digital from print) and many others. What? You think we read just for the music news?