Three weeks ago, Google filed its expected rebuttal to the European Competition Commission’s statement of objections released in April 2015. The EC alleges unfair competition in online shopping services.

My missive focuses less on the “what it is” and more on the “what does it mean”. Google blogged about the filing, but I haven’t yet seen the document. I choose not to source the blog, which is more about public relations. You can read the post by Kent Walker, general counsel, for yourself or the recap somewhere else. A Google blog recapping the filing is secondary to the legal document.

I asked the search and information giant for the filing and was directed to the blog post. I made a second request, to which a spokesperson answered: “We aren’t sharing the filing”. If the response surprises you, it doesn’t me. Google transparency only goes so far.

European officials did respond.”The Commission can confirm that it has today received Google’s reply to the statement of objections”, a spokesperson says. “We will carefully consider Google’s response before taking any decision on how to proceed and do not want to prejudge the final outcome of the investigation”.

Case Context

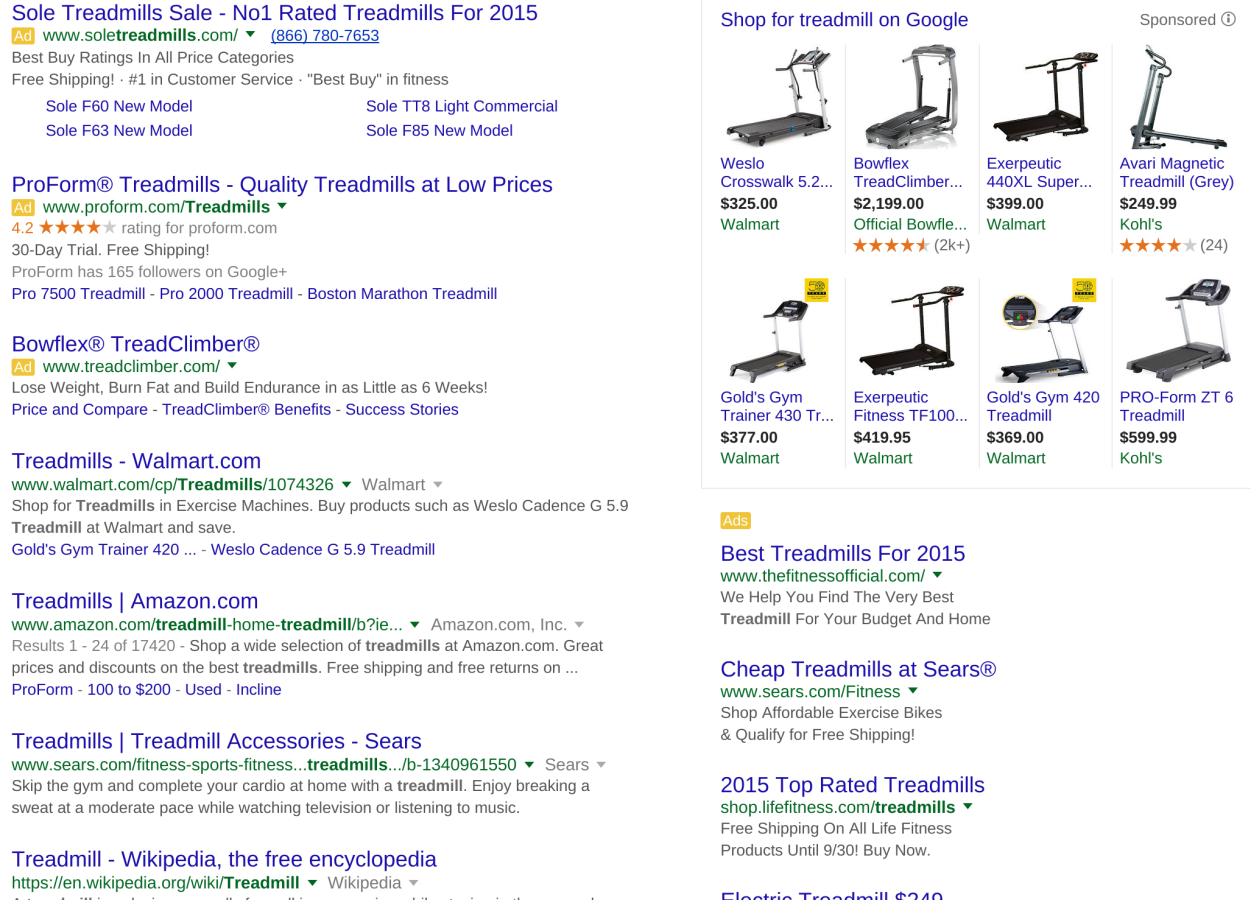

However, the European Commission’s case against Google and new investigation into Android are intertwined. Google’s business model copies and perfects what Overture (acquired by Yahoo in 2003) pioneered at the turn of the Millennium: contextual paid search. Shopping services are an extension. When users query for something that can be purchased, Google typically presents paid placements first. Take a look at the screenshot I captured today, as example.

Google presents organic results from retailers like Amazon and Walmart, but sponsored ads frame the results top and down the right column. These take prominent placement, and they are among the pillars supporting Google’s revenue stream. During second quarter 2015, for example, the company reported $17.73 billion revenue and $3.9 billion net profit. Advertising accounted for $16.02 billion, or 92.7 percent, of total revenue. Paid clicks on Google websites rose by 30 percent annually but only 10 percent sequentially.

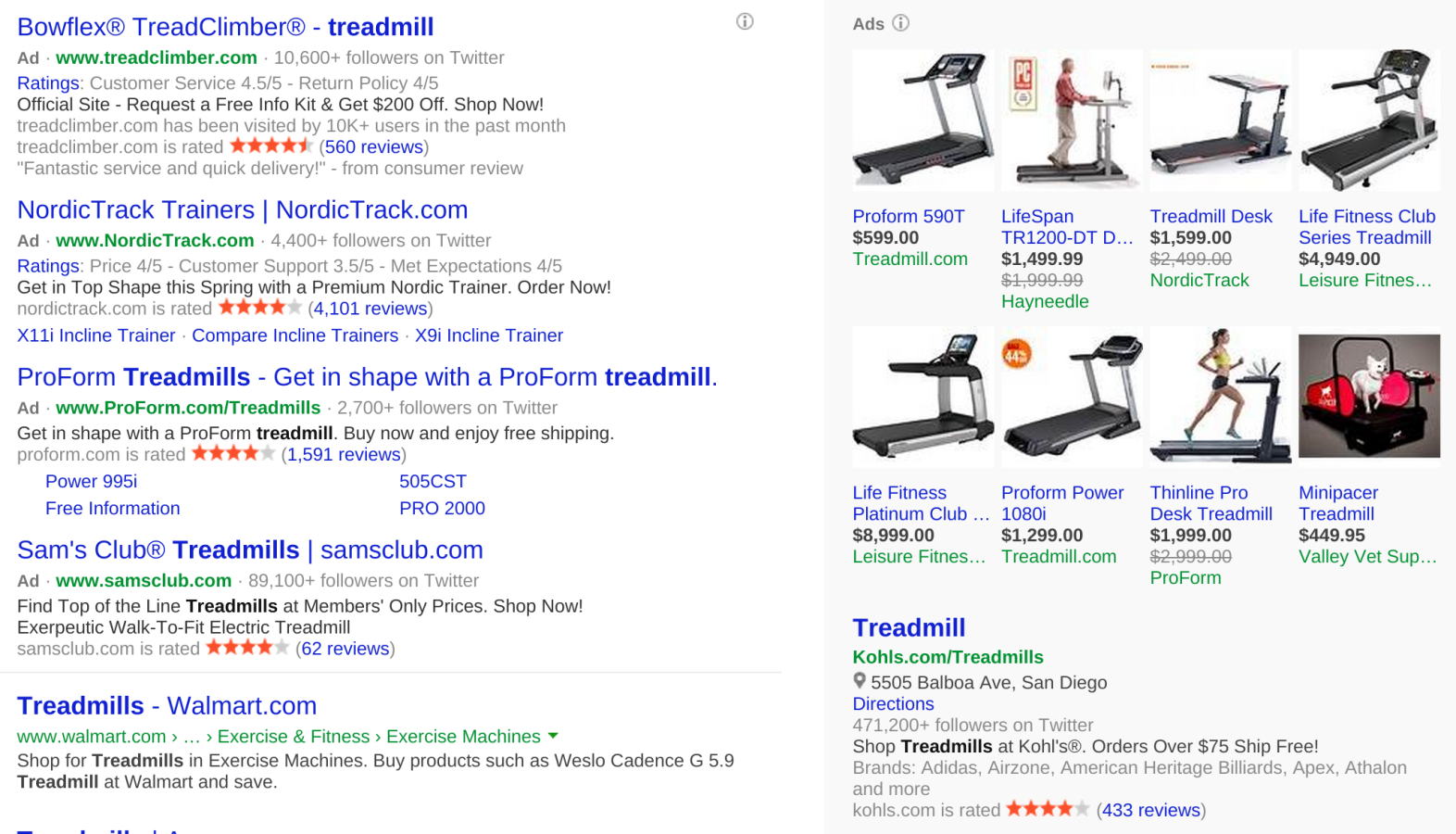

Other search engines present contextual and shopping advertising, too. The second screenshot is from Bing. The difference with respect to where ads are placed is striking. The Microsoft service puts even more paid ads in the main search column, and they are not as obviously paid placements as are Google’s.

The EC alleges that Google plays favorites with respect to shopping, something I can’t and wouldn’t determine based on the “treadmill” search or any other casually done. The point is something else: The Google Free Economy is all about profiting from someone else’s content given, or taken, for no cost. Google is not a search company (or subsidiary under recently formed Alphabet). It is a broker of information. Search is a means to an end, and that end is information.

Based on combined analyst data, Google’s search share in Europe hovers close to 90 percent and, by comScore’s measure, 67 percent in the United States. On the Continent, the company commands undeniable monopoly position. With overall revenues related to search-supported advertising exceeding 90 percent, the EC does due diligence by questioning the neutrality of shopping results. However, Google’s dominance, or the practices protecting it, is a matter of law beyond the scope of this analysis without today’s filing to review or opportunity for legal experts to evaluate.

Robot Rules

Android fits in as yet another monopoly, and one increasingly tied to search and shopping. The mobile operating system’s smartphone sales share, as of June, according to Kantar Worldpanel was, for example: 73 percent in France; 75 percent in Germany; 53 percent in Great Britain; 72 percent in Italy; 76 percent in Russia; and 88 percent in Spain.

Smartphones are the conquest Google and competitors like Facebook seek to make. The devices are more personal than PCs, are more likely to be carried, and can be geographically located for use with apps and connected services.

Consultancy eMarketer forecasts that global mobile ad spending will account for more than half of all digital ad spending next year, reaching $100 billion. The firm expects the number to nearly double by 2019. Meanwhile, purchasing habits are changing. In the United Kingdom, for example, about one third of retail ecommerce sales will be made on smartphones and tablets this year, according to eMarketer.

The potential bounty from mobile advertising and shopping is enormous, and pushing ahead is essential to Google keeping ad-dependent revenues high.

Users feed content into the Free Economy by way of their online behavior, and Google gives back through services like Google Now, which proactively provides contextually relevant information and tips. Location-awareness unlocks the benefits of search where the person is in real-time. The potential future of search and shopping is contextually-delivered ads about things users can purchase nearby that they already looked for online.

As Google advances into mobile devices, whether or not it oversteps what the EC or other regulatory agencies consider fair competition depends on several factors. Trust is core. Can you trust Google with your personal information? Will the company favor its own services or those of partners’ to maintain revenue flow from the 92.7-percent source?

A fortnight and a few days ago, Larry Page announced the creation of Alphabet, over which he is CEO and under which Google becomes a subsidiary. The entity seeks to expand beyond search and related services and long-term to open new revenue spigots that could lessen dependence on advertising. The risk that Google will abuse its monopoly position conceptually decreases when easing risks to its primary revenue streams. Meanwhile, the new organization opens expansion into innovations separate from search.

Stated differently: Google’s greatest response to the European Commission, and other regulatory agencies, isn’t legal but tactical.

Android Army

Android’s future role remains a wonder. Would Alphabet spin out the platform into its own subsidiary? One hypothesis the Free Economy series proposes: Separating Android from search, with some operational barriers between the two, would mitigate—possibly eliminate—the newer investigation in Europe. Otherwise, mobile’s bright future set against the market influence of conjoined monopolies paints a thousand-kilometer antitrust target.

I intimately covered the Microsoft US and EU antitrust cases during the last decade. Stateside, attorneys general concerned about the company leveraging its Windows PC monopoly into the adjacent browser market and the Office and Windows duopoly’s “applications barrier to entry”, as described by government lawyers. Android and search as free products subsidized by advertising and other services is duopoly and barrier to competitors, and even partners, trying to profit competing products.

Granted, Apple succeeds selling iOS devices but is nowhere in search compared to the market leader. However, the world belongs to Android, which smartphone share, measured in global device shipments, will remain above 80 percent when 2015 final figures are tabulated, according IDC. Stated differently: 1.2 billion handsets compared to 224 million iPhones.

As a business and logistical entity separate from search, Android could emerge as a more independent platform, even as OEMs customize and tweak it. Should such separation occur during this series’ run, expect a followup analysis with intelligent commentary from European legal experts.

Editor’s Note: This analysis first appeared on Byline, Aug. 28, 2015.