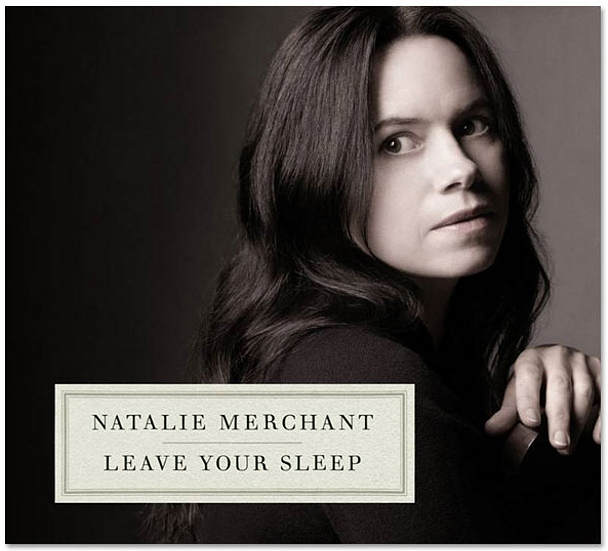

On New Music Tuesday, Natalie Merchant returned, with album “Leave Your Sleep”; her first in seven years. The amazing, 26-song collection indirectly comments on the value of public domain.

In the introduction from the liner notes:

This collection of songs represents parts of a long conversation I’ve had with my daughter during the first six years of her life. It documents our word-of-mouth tradition in the poems, stories, and songs that I found to delight and teach her. I pulled these obscure and eccentric poems off their flat, yellowed pages and brought them to life for her.

“Leave Your Sleep” sets numerous poems to music, and to a surprising splash of styles and genres. Many, but by no means all, of the poems are in the public doman, such as ‘Calico Pie” by Edward Lear or “Indian Names” by Lydia Huntley Sigourney. Natalie pulls together poems from nearly two-dozen poets. “Leave Your Sleep” is as much work of literature as music.

But art like this would be much more difficult to produce if onerous copyrights covered all the poems, or if their authors or descendants refused to grant usage rights. Copyrights are good within reason, but are they reasonable today?

England established copyright statutes in 1709. Founding Fathers of the United States continued them, using similar, sound approach: Grant a limited monopoly over a work of art, so that the artist or author could reasonably profit while also allowing for the public good; release the work into the public domain, within a reasonable timeframe. Since 1998, in the United States, copyrights extend 95 years, life of the creator plus 70 years or 120 years, depending circumstances.

April 10th-16th, 2010 the Economist commentary, “Copyright and wrong: Why the rules on copyright need to return to their roots” makes a good case for shorter time periods:

Copyright was originally the grant of a temporary government-supported monopoly on copying a work, not a property right. From 1710 onwards, it has involved a deal in which the creator or publisher gives up any natural and perpetual claim in order to have the state protect an artificial and limited one…

At the moment, the terms of trade favour publishers too much. A return to the 28-year copyrights of the Statute of Anne would be in many ways arbitrary, but not unreasonable…The value society places on creativity means that fair use needs to be expanded and inadvertent infringement should be minimally penalised.

Particularly in this era of social sharing and collaboration, when artists sample other artists’ works, relaxing of copyrights—even a return to 28 years, plus renewal—makes more sense than ever. Onerous copyrights restrict creativity and prohibit new artforms from emerging.

Human beings are natural communicators. Restrictive copyrights are unnatural because they interfere with the innate human desire to communicate, to cooperate, to share.

I publish this blog under a “Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike” license, because my belief is that information should be freely available to everyone. No one holds, or should hold, a monopoly on ideas. There is noncommercial restriction because I reason that if someone else is going to profit from my work, perhaps I should too. Share and share alike.