My first reaction to Amazon buying Whole Foods is “Huh?” Few brands could be any more different. The online retailer is all about giving customers the most for the least amount spent, while the grocer is the pricey purview of the alt-organic lifestyle elite. No moment is better metaphor for Whole Foods’ clientele than the exchange I heard between a thirtysomething couple standing at the deli holding chicken luncheon meat. “Is it free range?” the women asked her husband. It had to be, or she wouldn’t buy. They argued. I silently chuckled: luncheon meat—not a bird! It’s all pressed meat, Honey. You do know that?

But from another perspective, and one transcending retail store presence, are other considerations, like brand affinity and buyer demographics. For the first, Amazon may be all about value, but in an increasingly middle-class and well-to-do demographic kind of way, particularly among city dwellers. Despite sharing similar cut-throat margin, expansive business philosophies with Walmart, Amazon doesn’t carry the same stigma among the socially conscious “better-thans”. For the second, who do you think plunks down 99 bucks a year for Prime membership or can’t wait for two-day free delivery or is too busy to go to the store to buy groceries? Without hard numbers to back the supposition, I’d bet there is lots of existing and potential regular shopper overlap among these customers and those who walk Whole Foods’ aisles.

If Amazon just wanted retail presence, why not choose a chain with wider reach? Granted, Whole Foods is the Donald Trump of retail recently, meaning lots of bad press portraying dismal business and economic future ahead. Surely, that made the grocer a more appealing takeover target. But, to repeat, the purchase is as much about brand, and shopper demographics, as it is AmazonFresh’s potential expansion into broader markets. Both companies’ position core values (AMZN, WFM websites) that are important to people basing some of their brand allegiance on corporate values, not just value. Apple is another example of a socially-conscious brand.

Both entities stand to benefit from “better-than” professionals living in cities. Amazon gets more of their business, through the merger. Whole Foods expands its reach by way of Fresh deliveries and gets online ecommerce presence—something the grocery chain doesn’t have now.

As I always do, I write first based on my own analysis and then do a last-minute check before posting. Uncovered gem: Quartz’s excellent demographic exploration that uses data to make the similar point (and more surely): “Fully one-third of American households with annual incomes over $100,000 live within 3 miles of a Whole Foods”. Can you say AmazonFresh?

The immediate consequences are almost hilarious, considering the deal won’t complete until second half of the year. Stocks fell among major grocers today, following the merger news. Declines at market close: Costco (7.19 percent); Kroger (9.24 percent); Sprouts (6.29 percent); Target (5.14 percent); Walmart (4.65 percent). Whole Foods rose 29.1 percent to the close. Yikes!

Blame the Tax Man

My question: Who created this retail monster called Amazon? Obviously CEO Jeff Bezos and his minions deserve accolades. But what about grubby states, seeking more tax revenues? It’s my contention, with little corroborating data, that their greed turned Amazon from furry friend into beast.

Before California became the first truly large state economy to tax Internet sales (no disrespect, New York), Amazon kept modest presence here and elsewhere. By maintaining major operations outside the great bastion of liberalism—and dare I say stereotypically socially-snobbish Whole Foods shoppers—Amazon wasn’t required to collect sales tax. That all changed in September 2012, when California became the eighth state compelling Internet sellers to cough up.

Surely, Amazon worried that if people paid sales tax on online orders, they would choose to shop locally, as a major benefit disappeared. My family stopped shopping at the retailer, while keeping our Prime membership, for about six months. Then we resumed; speedier deliveries was one reason.

Sales tax collection meant that Amazon could now move distribution centers and other operations into and throughout the state and closer to points of delivery. Follow the timeline. AmazonFresh, which for six years had been locked to the Seattle area, ramped across California’s major metropolises: Los Angeles (June 2013); San Francisco (December 2013); San Diego (July 2014). Additional cities track through states that required sellers to collect sales tax on online sales. Coincidence? Yeah, right.

Take as another example Prime Now, which arrived in New York City for Christmas shopping 2014. Again, continued expansion largely tracks to cities in states where Amazon was compelled to collect sales tax on online orders, like Illinois, New York, and Tennessee. In other instances, October 2014, the retailer voluntarily started collecting sales tax in Maryland ahead of opening distribution centers there. Prime Now soon arrived in Baltimore.

Giant Grows

After resisting sales tax collection for so long—again, presumably in part assuming the consequence would be competitive disadvantage with local retailers—Amazon now embraces the activity. In April 2017, the online seller started charging customers sales tax in the 45 states and District of Columbia that collect it. There’s your precursor to today’s $13.7 billion Whole Foods purchase announcement. The grocer operates 465 stores, mostly across North America and in more than 40 states.

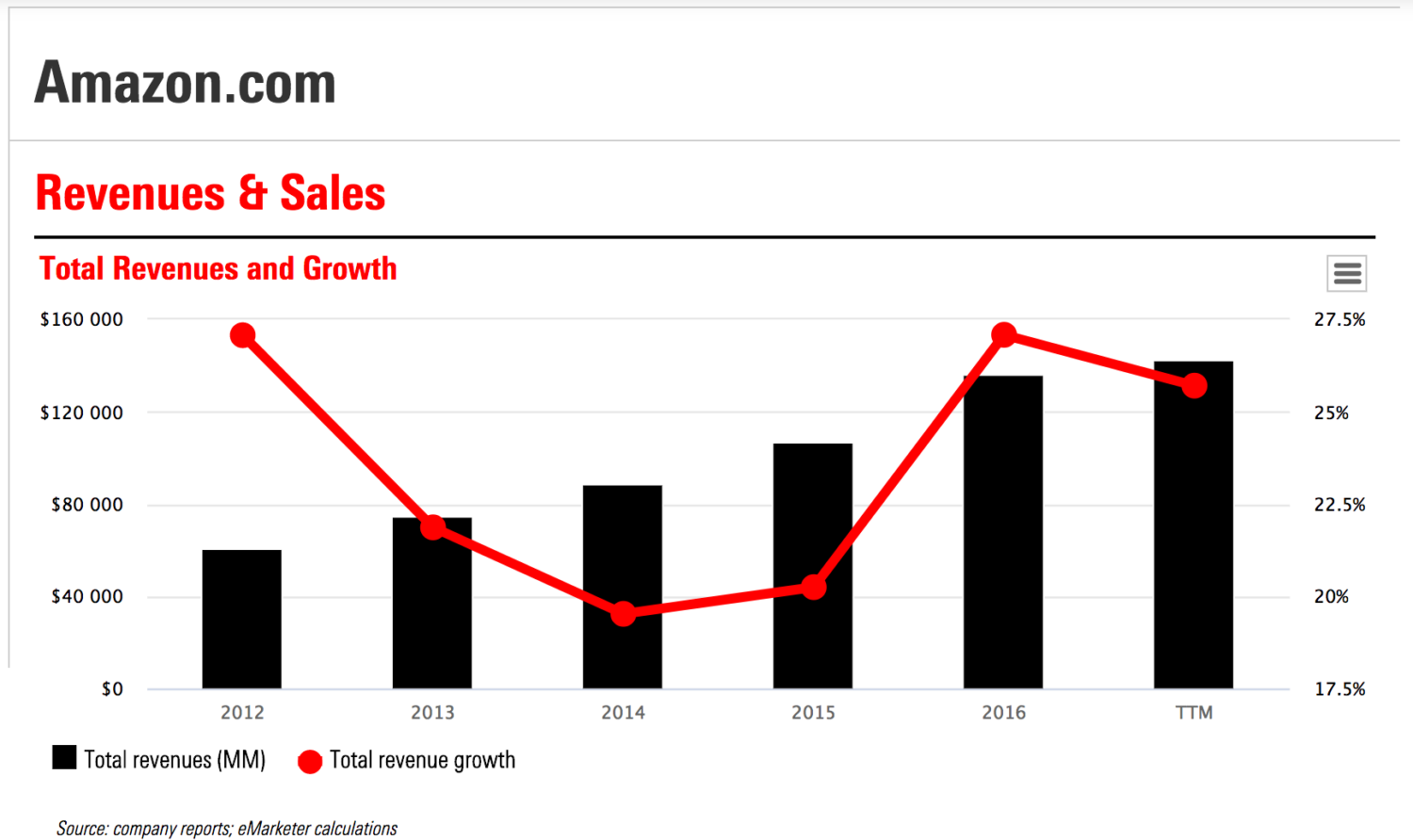

Amazon’s annual sales revenues tell the story differently, but convincingly enough. Sales spiked from $61.09 billion in fiscal 2012 to $135.98 billion in fiscal 2016. That said, based on data compiled by eMarketer, ecommerce sales declined as a percentage of revenue, from 84.7 percent to 69.6 percent during the same time period. Much, but not all, the change goes to Amazon Web Services growth: respective revenues of $1.84 billion rising to $12.22 billion.

Amazon has made many smart strategic moves during the last five years, with Alexa, Echo, increasing use of artificial intelligence technologies, and Prime Day among them. AWS is a major revenue pillar, too. But the expansion across America starts with the taxman’s greed, I hypothesize. The most important business changes followed: Putting Amazon facilities closer to consumers; relying more on U.S. Post Office and in-house delivery services; and making priority the delivery of more goods faster for lower prices.

What? What’s that? There’s an Amazon Drone banging at the window glass carrying a bag of groceries from Whole Foods. Okay, maybe not today. But too soon enough.

Photo Credit: Amish Patel

Editor’s Note: A version of this analysis appears on BetaNews.