The World Wide Web turns 15 this month, a milestone that simply shouldn’t go unobserved. Researcher Tim Berners-Lee created the first Web browser and server in November 1990, with little fanfare and based on acccepted standards.

The first Website wouldn’t come until August 1991. A 1999 Time magazine profile of Tim offers a great for-the-masses explanation of his work developing the Web and championing for the openness that made the network extensible and successful.

From a whole-purpose perspective, it’s not hard to appreciate the Web’s conception or its execution. Tim, who wasn’t the first person to conceive of a hypertext-like linking system, started tinkering on the Web concept in 1980, while working at European Organization for Nuclear Research (or CERN). It was there he would later bring the World Wide Web to life. The conception was unique, because of Tim’s decision to use open-standard technologies that no single entity controlled. Its execution is amazing because, according to Wikipedia, he made “his idea available freely, with no patent and no royalties due.”

Tim’s no-patent, no-royalty approach imbues the highest aspirations for what real research is supposed to be about. The patent frenzy of the last 10 years is phenomenal and antithesis of Tim’s approach.

On November 4, Arstechnica looked back on the Web happenstance that has revolutionized societies and commerce. Reporter Jeremy Reimer basically asserts that the Web could come to be because all the big companies were looking the wrong way. I totally agree with that position. The early Web, which hugely benefitted from its open-standards architecture, slipped through while companies like AOL, CompuServe, Microsoft and Prodigy built out huge closed-architecture, online networks.

In a November 2 Financial Times column, James Boyle takes a similar position. Sadly, I agree with the Duke professor’s assertion that “we probably would not create it, or any technology like it, today.” The way I see it: Companies like Microsoft, with heavily invested interest in closed, proprietary technologies, have worked pretty hard to co-opt the popularization of any open standards-based technology that might threaten their empires. They won’t let the mistake of the Web threaten their core technologies again.

Microsoft is a good example of the problem, in part because of its software monopolies, where one begets another. I hear Bill Gates talk about software innovation and transformation of the world as a better place. But I don’t see it. I do see the PC as infrastructure for creation and extension of the Web. And I see tremendous innovation continuing to sprung forth from the Web’s open architecture. I don’t see true innovation coming from new Office doohickies. Microsoft’s so-called innovation is more about preserving its proprietary technologies’ position. The company isn’t alone in taking such an approach. But Microsoft’s influence is so huge, the company is the most obvious example to use.

Publicly-traded companies like Microsoft would never give away something for free that could turn into the World Wide Web. This especially applies to successful companies that, either past or present, minted millionaires. My question: Whatever happened to aspirations for the greater good?

Software development was at one time more open, with hobbyists sharing ideas and extending them (It’s still the case for open-source proponents). In his famous February 1976 “An Open Letter to Hobbyists,” Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates accused: “Most of you steal your software.” Bill clearly wanted to be paid for his work, and later developed a fairly complicated licensing mechanism to ensure Microsoft received compensation that the company deemed fair. By the way, I find ironic that the “open” letter really argued for supporting a “closed” approach.

From the founder’s philosophical position—that starting point—how could a company like Microsoft ever demonstrate Tim’s open-standards or intellectual property approach? Never. And Microsoft isn’t alone, although some commercial software companies have “open sourced” some technologies, in part because of the development benefit they might receive from the approach.

The Web truly is a miracle, one of conception and execution, and one born of Tim’s goodwill and position as an academic researcher. I didn’t get on the Web until late 1994, using the Mosaic-based browser built into IBM’s OS/2. By late 1995, I had acquired my first domain and put up a Website, handcoding the HTML. I can still recall the excitement of going to Sun’s Website and seeing the little Java coffee cup move around. Funny, I usually had time to go get a fresh cup of coffee while that Java applet downloaded on the then super-fast 9600-baud connection.

In today’s New York Times, reporter Steve Lohr quotes Harvard Business School professor David Yoffie as saying, “Google is the realization of everything that we thought the Internet was going to be about but really wasn’t until Google.” I agree. New search technologies are truly extending the informational utility vision of hyptertext links.

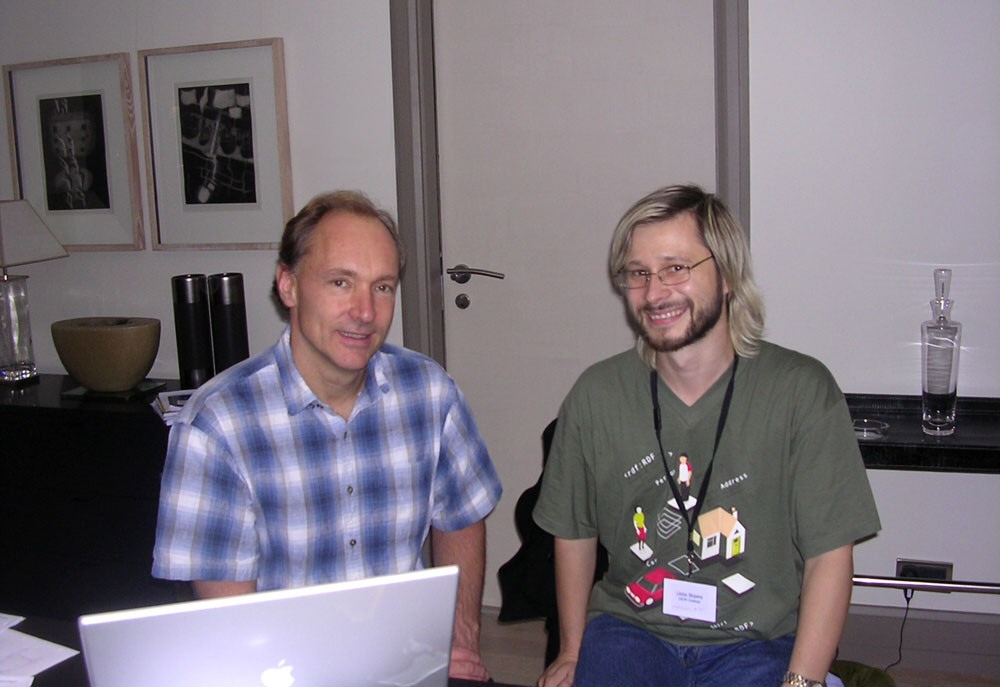

Photo Credit: Uldis Bojārs; Tim Berners-Lee (left) and Uldis Bojārs (right)