Microsoft has reached a surprising, and quite unexpected, fork in the road to its future. Choices the company makes today and over the next 12 months will determine whether computing relevance shifts away from its products.

The company has abandoned the fundamental principles that made it the most successful software company of the last decade and ensured its software would be the most widely used everywhere. Understanding those principles, and how they shaped Microsoft’s past, are important for understanding what the future might be.

I originally wrote a single post, but felt compelled to break it in two, because of the more than 2,500-word length. This first post focuses on the past, while the second is about the present and the future. If you want to link to either, rather than both, I recommend it be to “Micrhttps://joewilcox.com/2009/06/23/microsoft-has-lost-its-way-part-2/osoft Has Lost Its Way, Part 2.”

This post starts with early Microsoft history and success by way of establishing its technologies as adopted standards (subhead “He Who Controls the Standards Rules the World”) and moves on to the standards challenge posed by the Internet in the mid to late 1990s (“One Man’s Stand Against the Internet Tidal Wave”).

He Who Controls the Standards Rules the World

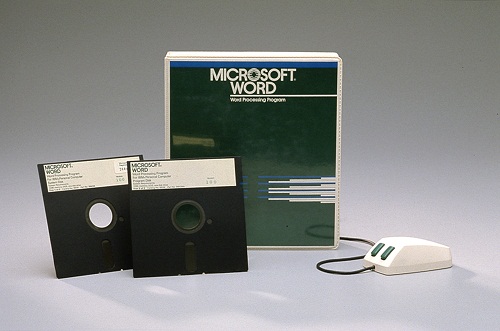

There are many reasons for Microsoft’s rise to computing giant during the 1980s and 1990s. Among them: Microsoft established Windows as a technology platform that became the standard around which developers and other partners supported products. In the early days, Microsoft’s approach was one of necessity: Maintaining standards compatibility with the IBM PC.

Microsoft owes much to one of its earliest OEM partners: Compaq, which announced the Compaq Portable—affectionately called the “luggable”—in November 1982. The 12.5kg IBM compatible PC went on sale in January 1983. The luggable was instrumental in opening up the PC clone market and widespread licensing of MS-DOS. Compaq’s IBM compatible PC also jumpstarted Microsoft’s reseller and OEM channels and precipitated the company to finally shift its fundamental business focus from programming languages to operating systems.

Compaq and Microsoft marketing and sales focused on two basic themes: Lower-cost computing and standards. For years, the companies shared common terms, “industry standards” or “standards-based computing,” which were code words for Wintel (Microsoft Windows and Intel) technologies.

Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates understood early on the importance of controlling standards and also file formats. In the early 1980s, Bill put Charles Simonyi in charged of productivity applications development. Early work done by the father of Microsoft Office achieved two important goals by the mid 1990s:

- Establish format standards resolving problems sharing documents created by disparate products.

- Ensure that Microsoft file formats would become the adopted desktop productivity standards.

Format lock-in helped drive Office sales throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s. Businesses needed Office to share documents and to maintain backward compatibility with a growing amount of their valuable information being stored in Microsoft file formats.

Microsoft’s control of Windows technology standards and Office file formats created a powerful deterrent for businesses or developers to choose competing products. US trustbusters called the Office-Windows dynamic the “applications barrier to entry.” They were right in this assertion, but so were claims by Microsoft executives that the company nevertheless faced stiff competition (see part two).

One Man’s Stand Against the Internet Tidal Wave

The most dangerous competition came not from a company but from a network. As Microsoft approached the ascension of dominance, trouble quietly came unnoticed, from the World Wide Web. Microsoft was looking the wrong way in the early to mid 1990s, with the company obsessed with competing with dial-up networks AOL and CompuServe. Meanwhile, a quiet revolution had started.

In November 1990, researcher Tim Berners-Lee created the first Web browser and server based on acccepted standards. The first Website didn’t come to be until August 1991. A 1999 Time magazine profile of Tim offers a great for-the-masses explanation of his work developing the Web and championing for the openness that made the network extensible and successful.

Tim started tinkering on the Web concept in 1980, while working at European Organization for Nuclear Research (or CERN). It was there he would later bring the World Wide Web to life. The conception was unique, because of Tim’s decision to use open-standard technologies that no single entity controlled. Its execution is amazing because, according to Wikipedia, he made “his idea available freely, with no patent and no royalties due.”

Why hasn’t Tim been awarded the Nobel Prize, for the Web’s transformation of business, culture and society? Sure he received the Finnish version a few years ago, but where’s the larger recognition. Surely it is deserved!

Bill Gates came to understand, finally, the importance of the WWW, and what it meant for his company in the months before Windows 95 shipped. His May 1995 “Internet Tidal Wave” memo succinctly identified the standards threat the Web posed to Microsoft.

Bill recognized the the Web used standards outside Microsoft’s control. In the memo, he specifically identified HTML, HTTP and TCP/IP. “Browsing the Web, you find almost no Microsoft file formats,” Bill wrote. He observed not seeing a single Microsoft file format “after 10 hours of browsing,” but plenty of Apple QuickTime videos and Adobe PDF documents.

Microsoft’s visionary founder warned: “The Internet is the most important single development to come along since the IBM PC was introduced in 1981. It is even more important than the arrival of the graphical user interface (GUI).”

In the memo, Bill laid out a counter strategy for maintaining Windows’ dominance and extending Microsoft’s control over emerging Internet standards. Some choice quotes explaining the strategy:

- “We need to give away client code that encourages Windows specific protocols to be used across the Internet.” [e.g., Internet Explorer, Internet Information Server]

- “[We must] define an integrated strategy that makes it clear that Windows machines are the best choice for the Internet. This will protect and grow our Windows asset.”

- “We need to establish distributed OLE as the protocol for Internet programming.” [Object Linking and Embedding later evolved into ActiveX.]

Microsoft aggressively and successfully championed standards that favored its technologies, such as SOAP (Simple Object Access Protocol) and XML (Extensible Markup Language). Microsoft’s approach carried it until around 2005, when the Internet winds started blowing in a new direction, and company executives, one again, were looking the wrong way. At Google.

Part two explains how in just three years, since 2006, surprising technology changes have put Microsoft in a tenuous position that executives seemingly have failed to recognize.

Photo Credit: Sergey Sokolov