This week’s turmoil on the streets of Tehran is but a metaphor for another turmoil: How the Internet is tearing down monopolies of power and empowering individuals and smaller groups. The Internet is the new democracy, which can be seen from pictures and videos coming from protests in Iran.

The Iranian protests are capturing the world’s attention in part because of fairly new tools that make it easy for most anyone to be a broadcaster, a real-time journalist. These tools punctuate change sweeping through the news industry and destabilizing others.

Survival Instinct Means Business

Capitalism is by no means democratic. Businesses and governments, which are formed by people, reflect the individual’s will to survive. These institutions have a survival instinct, which leads them to seek positions of power that will ensure their growth and protect their existence.

The news media is one monopoly of power. Massive news organizations collect information, which is printed, posted or broadcast for people to consume. Within these news organizations, individuals seemingly make decisions about what constitutes news and how information is packaged and distributed.

But these individuals really are part of a corporate mind, which seeks to survive. News editors and reporters make decisions that ensure the organization’s survival. It’s one reason why, for example, the Wall Street Journal might also cover a news item picked up by the New York Times or Washington Post. Editors tend to follow other news organizations’ stories for fear of being killed by the competition.

These news monopolies put the power to control and disseminate information into the hands of a small number of people. These people cannot avoid forces within their organizations or personal and cultural biases from influencing what so-called news they collate or disseminate. Journalism schools teach about impartiality, and news organizations claim to seek it, but the corporate survival instinct and cultural biases make impartiality more an ideal than realistically achievable goal.

Suddenly, news organizations are dying everywhere. They didn’t protect themselves, because the corporate minds felt safe and secure within their monopolies of power. They viewed their survival in context of their competitors, failing to see threat from Internet-empowered individuals who blogged, tweeted or vlogged.

Don’t Blame Craigslist

Craigslist isn’t killing newspapers, Internet democracy is. Sure, newspapers are declining in the United States, but not everywhere. In some countries, newspapers are growing. They’re gaining advertising and subscribers. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that in some of these same countries not everyone has Internet access—whether because of economic, logistical or political reasons.

The Internet democracy is killing newspapers and other news organizations; granted Craigslist is a part of that. The economics of news is changing, for which classified and other forms of advertising are smaller causes than many pundits claim. The primary influences:

- New tools let individuals self broadcast; they are the commentators or reporters.

- An increasing number of Internet-connected, audiovisual-capable cell phones lets anyone, anywhere be a broadcaster.

- These tools foster social interaction and commentary around news events. The people, not editors, choose what matters.

- The people flood the Internet with content, much of it now outside news monopolies’ control.

- The amount of content means that there is more online ad space than there is advertising.

- Supply and demand: Massive amounts of content decrease value for which advertising sells.

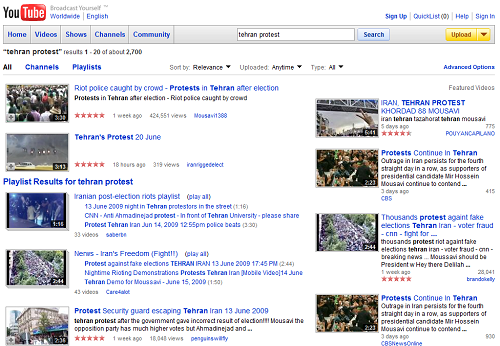

What happened on the streets of Tehran this week foreshadows dramatic changes, as citizens report the news in real time. The best reporting wasn’t from CNN or many news organizations but Flickr, Twitpic, Twitter and YouTube. The tweets (hashtag #iranelection), images and videos poured out in real time. Where is CNN getting some of its best material? Citizen journalists, like this story and images from CNN’s citizen-driven iReport.

But the videos—captured by compact digital cameras and cell phones—tell the story of unrest that only quieted today. Example: This 40-second video of young woman, Neda Soltan, dying. It’s seared into my psyche, like the image of the student standing before tanks in Tiananmen Square a decade ago. The video is raw and unfiltered. It’s the kind of footage that only a few years ago professional news organizations could capture and broadcast—and there would have been tight control over when and how it was broadcast and copyrights against redistribution. Now, people can self-broadcast to YouTube.

In Only Three Years

YouTube is now very much a part of global culture. Its influence is seemingly everywhere. But YouTube is but a recent construct, only going live in November 2005. Google bought YouTube about 11 months later—less than three years ago. Twitter also debuted in 2006, but only has reached mass awareness within the last 12 months. Facebook opened to the public in 2006, as well. Three years ago. Most of the most popular or growing popular tools for community and self expression launched within the last three years: Disqus, FriendFeed, tumblr, Twine, Qik and USTREAM, among many others.

My Nokia N97 smartphone came preloaded with Qik, a tool for live streaming from mobile handsets. What used to require a television camera crew can be done with Qik and a video-capable cell phone. Again, this is all from technology coming to market within the last three years.

As the people take their masses of content to the Web, news monopolies of power begin to crumble. There is too much content, and not enough advertising to support it. I’m a casualty of change. Nearly eight weeks ago, I lost my job as an eWEEK editor responsible for the Apple Watch and Microsoft Watch blogs.

Foolishly, many established news organizations are accelerating their doom, by laying off senior staff like myself and hiring younger reporters or freelancers to fill online pages. Their objective: To generate as many as stories as possible to generate as many pageviews as possible to sell as much advertising as possible. It’s a desperate move focused on search engine optimization rather than service to the reader. The approach is fundamentally flawed, for four basic reasons:

- These news organizations generate more content that looks much the same as other news organization content, diminishing its reader and advertising value.

- They add even more content to the clutter, increasing the amount of online ad space for which there isn’t enough advertising to fill.

- They further diminish the advertising value of their content and that of other organizations. There’s more supply than demand.

- SEO is a fundamentally flawed approach. The choice readers use social communities and RSS to get news. Headlines should cater to these readers not search engines.

A prediction: News organizations that adapt to the Internet democracy and produce original content will survive. Advertisers will want to be associated with this content; many readers will gladly pay for it.

The Econolypse’s Role

There is an important catalyst: The global recession, for which many monopolies of power bear much responsibility. The misuse of power is bringing many monopolies of power to ruin, even as governments seek to preserve them through costly bailouts. Months ago, I viewed the econolypse as being bad. But now I see it as opportunity. Many monopolies of power are collapsing, including businesses partly or largely responsible for the econolypse.

From their ruin, Internet-empowered individuals and smaller groups are a growing groundswell of discontent and self-determination. The auto and financial sectors probably could not be remade, hopefully for the better, if not for the global recession. They’re casualties of the economic catalyst. Other monopolies of power will collapse in similar fashion as news organizations, I predict. Television is on the shortlist, followed by the movie industry. The economics of these businesses are changing, as more content moves online and new tools allow non-professionals to produce more interesting content. By the way, Apple’s iTunes established a new music monopoly of power that helped preserve the old one.

I’m not convinced this Internet democracy is sustainable in a free market. The free market really isn’t free. Capitalism favors the creation of monopolies of power. From the ruin will rise new monopolies, I fear. Is it Darwinian—survival of the fittest? I think not. Monopolies of power are actually unnatural constructs. The laws of nature favor cycles of birth, maturity, life and death. Within the human family structure, for example, the parents nurture the children, who eventually replace them in society as they grow older. It’s a cyclical process.

Free markets seek to function that way, too. For example, when Microsoft was a young company, with few commitments or customers, it could move fast against mature IBM. Big Blue was an adult company, so to speak, with lots of customers and infrastructure to maintain. Today, Microsoft’s position is similar to IBM, because of Google, which is a young, rambunctious company with fewer customers and not the same technology legacy and ecosystem to support. Like a middle-aged person, Microsoft is less willing to take risks, for fear of losing customers or partners and thereby disrupting lucrative revenue streams.

That’s the cycle of business that most reflects human society. What’s unnatural, I say, not being an economist but studier of society, culture and human nature: Long-lasting monopolies of power. If capitalism doesn’t replace them through the cycle of life—eh, business—they give way or collapse through advancing industrialization. Human beings are natural inventors. Scientific advancement is inevitable.

The news business is undergoing a great turmoil, but that doesn’t have to be its ruin. In the early 20th Century, US doomsayers predicted that automobiles and airplanes would bring railroads to ruin. Actually, most railroads are quite profitable today. The railways no longer have a monopoly of power, but they do have a place cheaply transporting goods across America.

What’s different now is what’s replacing what. The technologies replacing rail fostered new monopolies of power. They were controlled by a small number of people. The Internet democracy is bringing control to the masses. People have speculated about the Internet’s role as a destabilizing force for more than a decade. The last three years of innovation suddenly accelerated into being something analysts long predicted. But that is topic for another blog post.

Let me close by asking you something. Because of non-traditional news sources, like Facebook, Twitter or YouTube, do you feel any more informed, any more in touch with what happened on the streets of Tehran this week than other recent international events? I sure do.

Update: Mashable has used the aforementioned social media tools to create a timeline of the protests in Tehran, starting with the presidential elections. It’s a good demonstration of the new journalism at work.

[Photo Credits: Steve Rhodes, protestor in San Francisco; Mehr via TwitPic, protestors in Iran]

Do you have a political or social media story that you’d like told? Please email Joe Wilcox: joewilcox at gmail dot com.