Paywall is suddenly a hot topic as free content turns many longstanding businesses—news among—to apparent ruin. News Corp. Chairman Rupert Murdoch is mad as hell, and he’s not going to take this anymore. This week Murdoch repeats his call for paid services during a U.S. Federal Trade Commission public workshop.

“We need to do a better job of persuading consumers that high-quality, reliable news and information does not come free,” he says. “Good journalism is an expensive commodity.”

But how is the value of the digital content, whether news or some other commodity, determined when so much of it is free? Bill Buxton, principal researcher for Microsoft Research, briefly addresses this topic during an October talk at the Business Innovation Factory.

“When the cost of goods approaches zero, the effective price inevitably for that product goes to zero,” he says. “We’ve seen it in music, and the music pirates—maybe they were bad, maybe they weren’t—were not causing it; they were just accelerating it. Every single other entity that goes digital has zero cost of goods. So, whatever’s happened in music is going to happen in literature, news, cinema, theater and so on.”

The prevalent theory is to fund all this stuff with advertising. “But if everything is going digital, going onto the Net, where is the money for advertising going to come from?” Bill asks. The Microsoft researcher cares about digital content going free, “because I can’t design an ebook [reader] without thinking about that stuff. Because I don’t want to design the most incredible experience of reading electronic things…[if] there’s nothing worth reading by the time I do it, because there are no professional authors, no professional journalists because they can’t make a living.”

A Free Web Advocate

Bill applies one view of economics—cost of production—to the value of content produced. Wired editor Chris Anderson puts forth another and one related in book Free: The Past and Future of a Radical Price. In a July 8, 2009, interview with WNYC promoting the book, Chris asserts that on the Internet “free really can be free.” Nobody has to pay.

“Google doesn’t show up on your credit card bill,” he asserts. (Actually its does on my credit card bill, once a year for Google Apps Premiere Edition.) Anderson supported his view, which does allow for combo free and paid models, by way of marketing and economic history and theory.

But I don’t agree with Chris’ economic construct or Bill’s even though I agree that the value for all content is in rapid decline. Contrary to popular belief, economics doesn’t derive from human culture or society, but from the natural world—where nothing is really free. Air doesn’t cost you anything. It’s free; natural processes over billions of years paid for the atmosphere we freely take for granted. But the process of breathing isn’t free. It requires the proper functioning of interdependent biological systems and input of energy, provided by ingested food. There’s always some price.

The same principal applies to human society. For example, as an American I seemingly drive on the highway for free. But that free is a deception. I didn’t pay to build the highway, but sales, state and federal taxes—including the gasoline fueling the car—pay to maintain the roads. The price is hidden, but it’s there.

My point: Nothing is really free. Somebody pays. But with the Internet and proliferation of seemingly free content, will online consumers pay fair value for producing it? That question is at the core of Murdoch’s desire to erect more paywalls and his threats to pull out of Google search indexing.

Modern economic theory is too hung up on prices, when value is more important. Often pricing is independent of value, as should be apparent from the housing market collapse. An artificial debt-driven bubble drove up home prices, which didn’t make the real estate more valuable. For a teen the value assessment might be: Is it worth cleaning my room so my parents won’t yell at me or will I get more benefit from chatting with my friends online? There is an associated value assigned to the action, but not an associated price.

People will pay for anything for which there is perceived or actual value. The problem with digital content is the overwhelming access to stuff produced nearly at no cost— whether pirated music or aggregated news—for which online users find enough value. They aren’t willing to pay.

Gatekeeper to the Web

I sometimes blame Microsoft—and its competitors even more—for this free-out-of-control mess. In March 2001, the company outlined and ambitious Web services strategy called HailStorm. I wrote for CNET News.com:

HailStorm is a group of services, using Microsoft’s Passport authentication technology, meant to provide secure access to e-mail, address lists and other personal data from virtually anywhere via PCs, cell phones and PDAs (personal digital assistants). The catch? Users of the services will be required to pay a fee to use them. Analysts said that if the HailStorm model is widely adopted—and if people will pay a premium for security—the days of ad-subsidized Internet services, such as free e-mail and messaging, may be over.

Microsoft planned to make Passport authentication—and the paid services they would enable—broadly available. But within a year after the announcement, Microsoft abandoned HailStorm and pulled back its ambitious single sign-on authentication system. Security and privacy concerns and business and technology limitations were among the reasons.

Perhaps most significant: Competitor attacks—what I call competition by litigation—by way of legal complaints filed with the U.S. FTC and Justice Department. The prevailing theory: Microsoft would become gatekeeper to the Internet, if not checked.

A gatekeeper did come. Google is the master of free, around which it makes billions through keywords, advertising and other services related to search. Google search is the means by which most people access Internet content, for free. Free access, supported by SEO (search engine obsession)-driven aggregated digital content, creates perceptions of value—what the content is worth. Too often, nothing is the value. But even that search-engine found content comes from somewhere. Somebody pays to produces it.

Perhaps if the content was harder to get at, such as going behind that paywall, people would value it more. That is if they can find it through search. Paywall content might not be accessible through search. Applying the old tree-falls-in-the-forest axiom, does content that nobody can find through Google really exist? How can someone pay for something they can’t find?

During the Business Innovation Factory talk, Bill told of having content in a book changed because the editors couldn’t verify the information via Google. The contentious issue: Who invented the chalkboard—or in the nineteenth century what was called the slate. “I realized, ‘Oh, crap. We are screwed,'” Bill says. “If it’s not on Google, if it’s not on the Internet, it doesn’t exist.”

Editor’s Note: A version of this analysis also appears on Betanews.

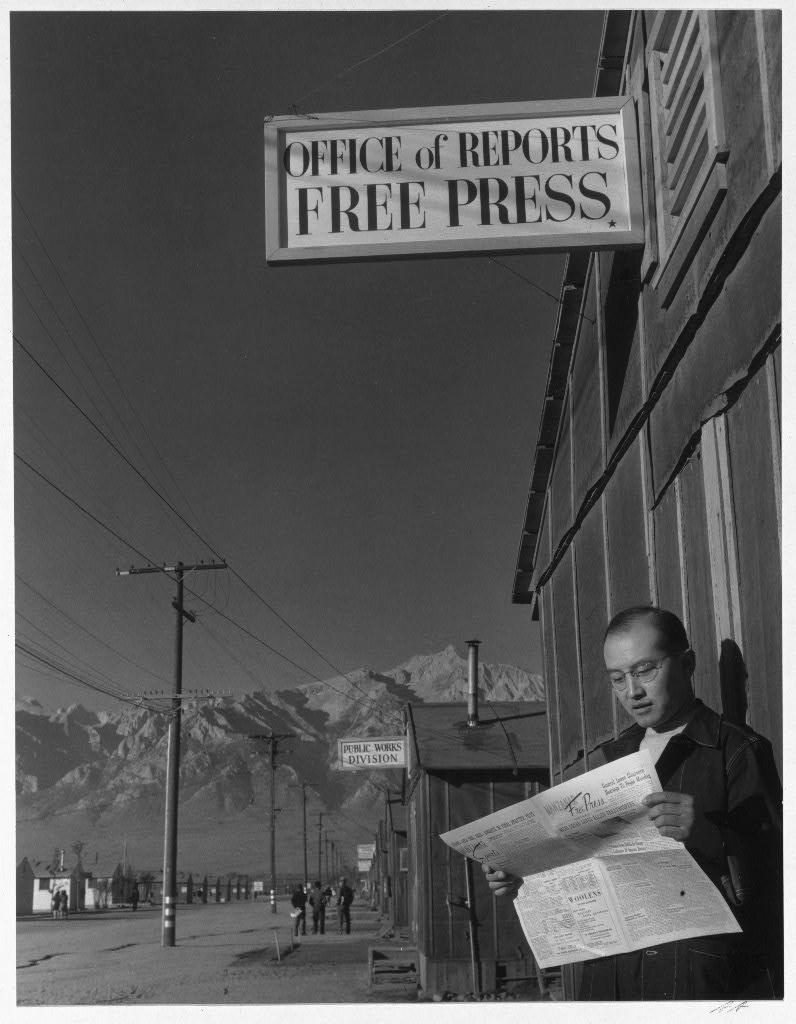

Photo Credit: Ansel Adams (Courtesy U.S. Library of Congress)