Yesterday, my first ebook published to Amazon, with the strangest of titles, having nearly nothing to do with the contents. In May, I submitted “The Principles of Design” to the bookseller for consideration as a Kindle Single. Singles are curated, short-form works, between 5,000 and 30,000 words. Amazon acts as editor and publisher. Four weeks later to the day, I received a rejection letter, without any explanation.

That put me squarely down the self-publishing path, which is exactly where I didn’t want to be for this first work. Books are a strange frontier to me, a vaguely familiar landscape but alien—like Mars is to Earth. I wanted Amazon to walk me across this domain. Besides, to start, I plan to write mostly shorter non-fiction essays, which look to be perfectly-suited for Kindle Singles. But the rejection email, and realization that editorial approval takes up to a month, changed plans.

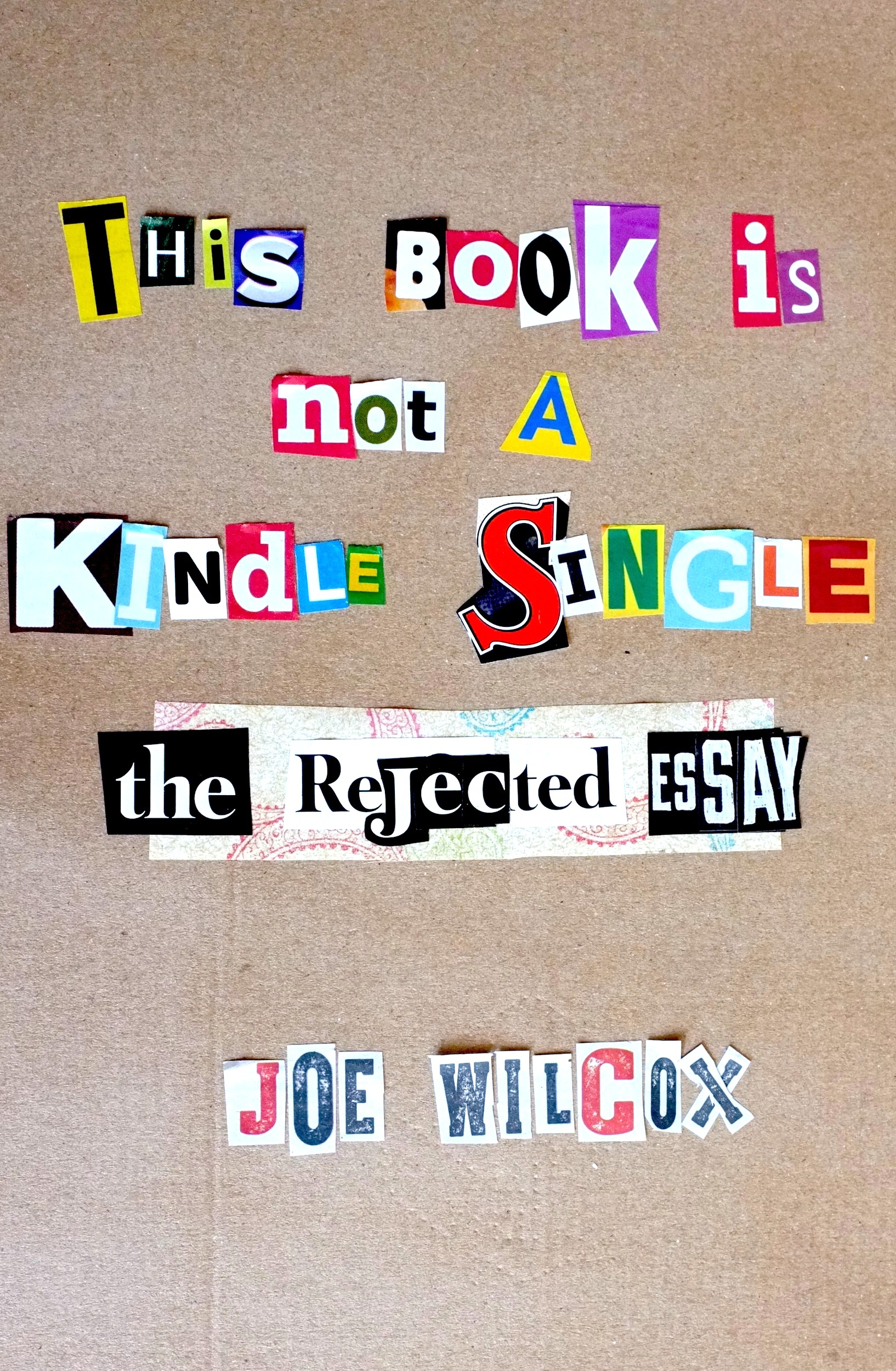

So, with a little Amazon-poking in mind, I re-titled the work: “This Book is not a Kindle Single (The Rejected Essay)”. When the 90-day exclusive with the online retailer ends, I will publish at other bookstores under the original title.

While I am satisfied with the essay, it’s really a beta test. I needed to go through the whole self-publishing thing with something, and for good reason. The process of formatting for Kindle’s MOBI proved to be as challenging as some writers warned. I principally used as reference: APE: Author, Publisher Entrepreneur—How to Publish a Book by Guy Kawasaki and Shawn Welch; the guide is indispensable.

I wrote the draft submitted to Kindle Singles on Chromebook Pixel using Google Docs. Between that version and the final, I briefly switched to MacBook Pro with Retina Display. But as explained last month, I switched back to the Pixel. For many reasons. Principally among them: Creative writing. The best book publishing tools are supposed to be available for OS X and iOS, and that’s true from a maturity perspective. But I lost writing momentum; the Mac just doesn’t fit anymore. There is something about Chromebook Pixel that puts zing in my writing, and ironically it relates to the topic of my book.

There I articulate eight Principles for disruptive design, the kind that changes or creates new tech product categories. Pixel better meets these Principles than does MacBook Pro—at least for me. Good writing is about identifying an audience and crafting works for them. Product design is similar. It’s like Google designed Pixel with writers in mind:

- The keyboard is the best I’ve used on any computer

- The 3:2 screen ratio (rather than 16:9) is better for viewing web content

- Google Docs is less-cluttered and distracting than typical word processors

- The high-resolution display, combined with excellent font, improves reading and writing

- Working in Chrome puts everything, including research, in a confined space, reducing distraction and improving concentration

My productivity is much better on Pixel than on MacBook Pro, despite the Apple computer offering more mature publishing tools. The Google laptop conforms to more of the Principles of Design, particularly ethics about reducing complexity and increasing simplicity.

That said, just about every ebook writer I consulted (thanks for your blog posts, all), recommended Word. So I used the software on the MacBook Pro for final production stages. Oh what misery was moving from Docs and Pixel. I won’t do that again. My next book, publishing later in August, will skip Word altogether.

Besides, despite days of production drafts, formatting isn’t perfect. I had to remove bullets from bullet-lists. There is no link-to Table of Contents from the Kindle Reader drop-down menu (but there is one in the books’ front). There are extra paragraph spaces here and there throughout.

After looking at Amazon’s delivery charges (15 cents per 1MB) and heeding the APE authors’ warnings about formatting problems when adding more elements, I published straight text, which was not my original plan. Because I expect lower sales from the first edition, for lots of reasons (being a new author among them), I chose Amazon’s higher royalty rate, 70 percent, which incurs the delivery charges. The lower, 35-percent royalty does not. This book really needs illustration, something I will include in the future, revised edition.

Buyers who brave the dense text won’t be cheated. I will update the book in November and February, at the least, with the newest analyst numbers. My goal is to keep any content with dated material current, which is important for an essay where so much has long shelf life. This is the magic of ebook publishing over print: The ability to update a work; keeping it current; and readers receiving the changes.

I asked my wife, who is a graphic designer by profession, to create the cover art by hand, rather than computer. My instruction: Make it look like a ransom note, which she did. I shot the cover using the Fujifilm FinePix X100 “Special Edition“. Last week, I bought the Eye-Fi Pro X2, which wirelessly posts pics to a private online folder and also sends them to my HTC One; that’s better for someone using a computer where Chrome is the main user interface. I had spiced up the ransom note cover, during editing, but it proved illegible when reduced to small thumbnail size, which is what most people will see on the Kindle Store.

“This Book is not a Kindle Single (The Rejected Essay)” is part of the Kindle Direct Publishing Select program, which means the aforementioned 90 days exclusivity and, for readers, availability in the lending library—a free benefit to Prime subscribers. I also can make the book available for free for five days, which I will spread out over the next few months.

Why give away a book for free? Exposure, which is particularly important for new book authors like myself. Free-lending or giveaways can raise a books ranking on Amazon, while bringing in reviews about the work.

Why should you get this book? I explain what attributes make, for example, Apple products so successful and explain why Google is the emerging leader in disruptive designs. “Google stands apart for pushing forward Star Trek-like human responsiveness”, as computing and consumer electronic devices move from touch to touchless interaction. I see and explain why, for example, the Moto X smartphone promises to be as category-changing as the original iPhone.

The reading is a little dense, because so much information packs in, but worthwhile. Of course, wouldn’t every author so boast?