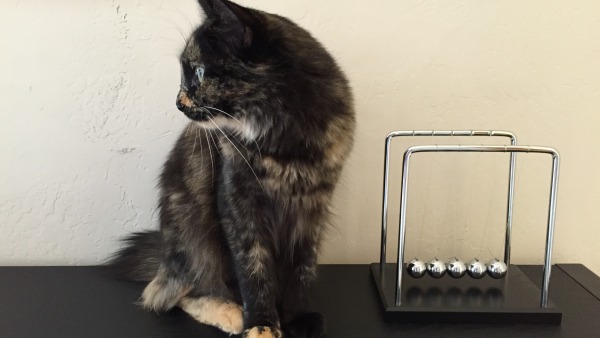

On October 20, my daughter’s cat Cali moved into the Wilcox domicile, where she and our other feline Neko slowly, but surely, adapt to one another. The kitty is the second to adopt my now college-age child and chance for some redemption for the first.

I met Cali on a pleasant summer evening in early June. Molly—that’s my daughter—moved into a group house, and I had just dropped off a last load of belongings. As I crossed the street to the car, a slim Tortoiseshell cat approached down the sidewalk. She raised her head to receive pats, just as a San Diego State University senior approached. He and I chatted about education and careers for about 15 minutes. Then we parted from one another and our new feline friend.

The next morning, Molly excitedly texted about a cat coming to her bed and sleeping all night; the feline squeezed through the cracked-open sliding door that leads from the bedroom to the backyard patio and pool. A photo followed, of the same cat that greeted me. The Tortie had no obvious home, and she may have been abandoned or lost when other students moved from the College Area around June 1.

Molly gave the name Cali, which here, in the new home, she doesn’t respond to. I’m no good at judging a cat’s age but could see in June this one was a large kitten not much older than 6 months. Cali took up residence in and around Molly’s new home, spending much of her indoor time with my daughter in her bedroom. My daughter named the cat Cali thinking she was a Calico, as did I. The kitty is a Tortoiseshell.

Leo’s Story

Around the same time of year, in 1998, another growing kitten adopted Molly. We moved into a rental house, located in Kensington, Md., a few months earlier. A grey tabby often visited, but as the weeks went on he looked scruffier and started begging for food. So we occasionally fed our visitor, whom the landlord forbade from being in the house. “No pets!” His collar tag read “Dap”.

One day the collar disappeared, and I observed him hanging around more frequently. I asked a neighbor about Dap, whom she said former residents two doors down abandoned. Molly renamed him Leo, which he fairly quickly learned. He chose us as owners, but we couldn’t—sadly wouldn’t—give what he needed.

Leo was a house cat forced to live in the street. He longed to live inside, and he kept vigil by the sliding doors that led from basement to backyard. We placed food and water dishes on the other side of the glass, but shoed him out after darting in. He suffered some harsh Maryland winters, during which we brought him inside for a single night, during an ice storm. To shelter Leo, we put out a little cat house, with cozy warmer. But during snowstorms he often headed in the direction of a neighborhood’s shed, where I assume he slept. Occasionally, I would see him come out of a rain gutter.

If ever there was a lap cat…he would jump on any of us as we sat in the backyard. He relished pats and lapped up any attention. Our long-resident stray was constant companion during any activity, even cutting the grass (with a non-motor push mower). When we vacationed, someone always fed Leo and refreshed his water—typically one of the neighborhood kids, whom we paid.

Leo was gentle, almost to a fault. Many nights, I would see him keeping vigil outside the glass, alongside a possum or raccoon eating his food. We chased away other cats, which stole from Leo, too.

Seven years after coming to us, Leo stopped eating, so we put him in a thrift-store cat carrier and carted him off to the veterinarian. She made her amazement clear, that he had lived so long on the street, and, after conducting blood tests, that he hadn’t contracted feline HIV. Leo had a respiratory infection, and the vet wanted to put him down. The tears flowed heavy in the examination room. We loved him, after all. Leo was a part of our family, although not the best cared for member.

I can’t speak for my wife or daughter, who might have taken the vet’s recommendation to end his suffering. I was resolute. Choking back tears, I told them: “We should fight for him”. We carried languishing Leo home, and I administered an antibiotic, hoping he would recover enough to resume eating and drinking, something cats won’t do if they can’t smell—and Leo couldn’t. Looking a little gaunt, he started consuming again a few days later.

If I could go back in time, I would defy the landlord and let Leo live inside as well as outdoors. I would change something else: A second family abandoned Leo, not that we intended to. I would so change that, too.

In October 2007, we moved from Maryland to California, to be closer to my then 85 year-old father-in-law. We couldn’t take Leo. That Kensington neighborhood was all he knew, where he lived for a decade—70 cat years. I desperately sought a home for him. At that time, and I presume the policy remains, the local animal shelter euthanized unadopted cats after 21 days. He couldn’t go there. I pleaded with the local humane society for assistance. The woman said no one would adopt a 10 year-old cat. She made her shock clear about his long life, stating 5 years is typically the longest any feline survives on the street.

The SPCA wouldn’t take him for adoption but found someone who wanted a cat. Funny thing, the San Diego branch has a different policy and welcomes aged animals. I typically see cats older than Leo—some 15 years-old—waiting for adoption. But in Maryland, the Humane Society rejected Leo. I saw the distress in his eyes as he was taken away in the thrift-store cat carrier and immediately regretted, but I felt helpless with our departure so close and options so few. The phone call came hours later. Leo escaped. He didn’t want to be just anyone’s house cat. We belonged to him.

Leo’s loss came two days before our departure, and I drove through the neighborhoods looking for him. I meant to preserve his life but in hindsight would rather have euthanized our outdoor friend, letting him go with love and dignity. He was devote, supremely loyal, and we betrayed him.

Cali’s Story

There is no way to change how we wronged Leo, whom by feeding and loving we assumed responsibility. But I hope, that by caring for the new stray, some redemption is possible. Yes, he was only a cat but special, too. Leo lived long outdoors, and I always felt that by presence—patiently and loyally waiting on the other side of the glass—he somehow protected our family.

So we have Cali. The kitty comfortably stayed with my daughter, lounging outside the pool or in the front yard, until late August. Five women live in the house, and the last moved in just as school started. I don’t fathom college group house dynamics, and my daughter refuses to explain them. The final co-ed wanted the cat, and cutest dog I’ve ever seen, gone. The women discussed the animals’ disposition in early September, voting four-to-one to keep them. So much for the democratic process, because the single vote carried the decision. The cat and dog had to leave within two weeks.

So on another Sunday in September, while I foolishly expected Cali to stay put, the edict came: Must go. Now! One of the other roommates whisked the cat to her family home, where I expected the kitty to live. But the move was temporary, for reasons my daughter doesn’t explain. We picked up Cali on a Monday morning and took her to our veterinarian before taking her to a new home.

She is a long, skinny cat, weighing 3.3 kilos (7.2 pounds) at the vet and measuring 53 centimeters (21 inches) from forehead to rump by my ruler. As expected, she wasn’t chipped or neutered, and the veterinarian estimates Cali’s age to be close to one-year. To chip, the cat doctor wants $50 and $350 to spay, plus another $65 for recommended blood test. Hell no, to that. We did spent about $150 on shots and the feline HIV test.

One week ago yesterday, the San Diego Humane Society and SPCA chipped Cali for $10, but we gave Twenty—the extra as donation. She is scheduled to be spayed in mid-December, for which the fee will be $50. Molly’s income and status qualifies Cali for the much-reduced fees.

The plan is to, for the foreseeable future, keep the Tortie indoors. On Jan. 15, 2012, our Maine Coon Kuma disappeared, presumably taken by a coyote. We live too close to a canyon to keep another indoor-outdoor cat. Besides, Cali doesn’t know us or this neighborhood, and, indoors, there is little risk of her becoming pregnant before her near-Christmas spay (terrible present, eh).

Our nine-unit apartment complex looks out onto a lovely courtyard, where in late-August we started taking out our other cat, Neko, whom we acquired from the San Diego Shelter two months after Kuma disappeared. Neko, whose name means “cat” in Japanese, had grown lethargic and large. We hoped the outdoor romps would lift his mood and push down his weight. The risk: He can slip under the back gate, but, so far, either my wife or I standing before it has taught him not to go through—despite enticing birds in the alley.

By contrast, I look at the courtyard and see at least a dozen escape routes for Cali. She’s skinny enough to slip under either gate or the fence and climber enough to go over either. Neko still gets his morning outdoor jaunts, while Cali plays with one of us behind closed doors.

She meows to go outside, and the adjustment isn’t easy—taken from her familiar outdoor neighborhood and the territorial lifestyle established with my daughter, all while going into a new home where strangers and, gasp, another cat resides.

We started out Cali in our old bedroom, which had lost purpose after Molly moved out. She took the parent’s bed frame, and it was easier moving our mattress into her old room, where also I write. We established the bedroom as Cali’s territory, and kept the door closed and Neko out for the first four days. We moved in an end table, covered with a blanket—Cali’s cave—which particularly during the first days created an enclosed space where she could feel safe. A desk and settee provide some high ground, plus there is an IKEA shelf nearby the window that looks out onto the alley. Neko has bit better view in the next room from a cat tree.

Molly’s old room is a Cali-free zone, so that the male keeps some territory of his own. The Tortie has no such luxury. Neko is accustomed to sleeping in our old bedroom, and he is most interested in the new resident. He drinks from her water dish, and, to my surprise, the animals share the two litter boxes—hers in the bedroom and his in the bathroom. My wife, Anne, sleeps in Cali’s room with the door closed and will do so until we feel the cats can be let loose unsupervised at night.

In the main living area, the cats share space, but we purposely demarcate personal territory. A red IKEA table sits below a small window in the living room, flanked to the left by the front door and to right by sliding door leading out onto a balcony—all in tight proximity. We keep Cali off Neko’s table, preserving that beloved territory for him, while either cat can sit and look out the open doors; they often are open, being this is sunny San Diego. Also, in the dining area, we established an IKEA shelf, like the one in the bedroom, for Cali to look out into the alley, where many birds gather. The view is as good as from the cat tree, and Neko is too, ah, large to leap up to the space.

When bringing a young kitty into an older cat’s territory, it’s important to preserve as much as his routine and space as possible. The animals should start out separated, with integration progressing. For us, that process started just four days after Cali’s arrival. She was ready to venture out, and he in.

The two cats tolerate one another, and there is increasing interaction that usually means chasing around the other. The behavior looks aggressive to me, but there is something playful about it, too, and so far fighting isn’t a problem. I’m convinced these two felines can not just coexist but cohabitate intimately. The process of our defining territory seems to be working. Fingers crossed.

Already, they are moving in sync. When Cali first arrived, she kept an active day schedule while Neko slept. But the longer she stays, the more their times of sleep and wakefulness coincide.

Cali’s habits are rather perplexing. She eats greedily, like a starved beast. She doesn’t so much chew soft food but suck it down. The feline finishes her portion even before Neko is served, so fast she sometimes gets to his dish and empties it before he can. If he is close, she growls while eating.

Then there is drinking. Molly once mentioned never seeing Cali drink water from her bowl and worried the cat preferred the swimming pool. In our apartment, she goes to either the bathroom or kitchen sink looking for aqua. If I place out a bowl of water, she ignores it. But if I pool water in the bathroom sink, she sometimes drinks. Cali prefers to take water from the running tap, a behavior I’ve seen in cat videos but never up close. However, while writing this post, Anne saw the kitty slurp from her water dish for the first time.

Neko likes to kneed his paws on a blanket. Cali does the same on your belly, with her tail and butt turned towards you. When finished, she will tap her head to hand for pats and lie down with her nose against your chin. Then it’s sleep time, although she takes most of her naps inside or on top of her cave.

There’s something needy, not kneedy, about Cali. While she bears no physical resemblance to Leo, she still reminds me of him. He needed, too, and in ways we failed to give before showing such disloyalty to one so loyal. It’s no coincidence, because I believe in none, that these two abandoned animals adopted Molly. Maybe in an alternate universe, I did better for Leo. In this one, I can do something for Cali.