I am a committed practitioner of Occam’s Razor, which adapted to my troubleshooting thinking translates to something like: A problem’s simplest solution starts with answering “What changed?” Applying that principle, I honed in on a simple, specific cause of my daughter’s lethargy. I stepped back from my obsession about dialysis and asked the question. Answer: She started receiving antiseizure medicine the day before her sudden sluggishness.

Recap: Last night, I explained that our daughter is in one of the local hospital’s intensive care units. To be clear, I won’t turn this blog into a blow-by-blow account of her recovery (whatever that may be). But open-ended story about her plight, and today’s happenings, are reasons for quick follow up.

At 7:21 a.m. PDT, today, I called the ICU and spoke with the attending physician regarding my theory about the hypothesized effects of the medicine. She said that the neurologist on duty coincidentally specializes in seizure disorders. She would consult with him.

A few hours later, I arrived at the hospital to some surprises. For starters, on the white board in our daughter’s room, extubation was on the of list of activities, tests, or treatments. She had been breathing on her own for more than 24 hours and removing her from the ventilator was proposed.

Not long later, the attending doctor approached me. She had contacted the neurologist, who would come by later to discuss the antiseizure medicine and to evaluate our daughter’s alertness and responsiveness to commands. The physician was willing to extubate, explaining the risks. We agreed to hold any final decision pending the neurologist’s arrival.

Meanwhile, the nephrologist appeared. He explained that dialysis would once again be delayed (but this instance not because of staffing shortages). I inwardly groaned, then did an internal about face when hearing the reason. Our daughter’s urine output had returned to normal volume overnight, and additional treatments might not be needed. Scolding myself, I had banked too much on dialysis when “What changed?” should have been my question.

Sometime after lunch, the neurologist swaggered into our daughter’s room. He brought great attitude that was sorely needed. Initially, she responded limply to him as she had to everyone else. Then he bellowed her name. In loud, commanding voice he issued instructions to which she followed. He was satisfied.

As for the antiseizure medicine, he ordered it stopped. The weekend’s EEG showed no seizure activity and he doesn’t like giving this particular drug to patients with kidney problems. He wasn’t surprised that she slept all the time after receiving it. He closely enough proved my hypothesis. Like our daughter gave literal thumbs up to the neurologist’s commands, he gave figurative thumbs up to taking her off the ventilator.

A few minutes after three, our daughter was extubated. With eyes closed, soon as the arm restraints were undone, she brought her arm to the side of her heard and touched her lips with her fingers in a self-examination of sorts. She slept, or pretended to, but either way I decided not to stay late and left before 5 p.m. Let her recover and rest. Many difficult days are ahead.

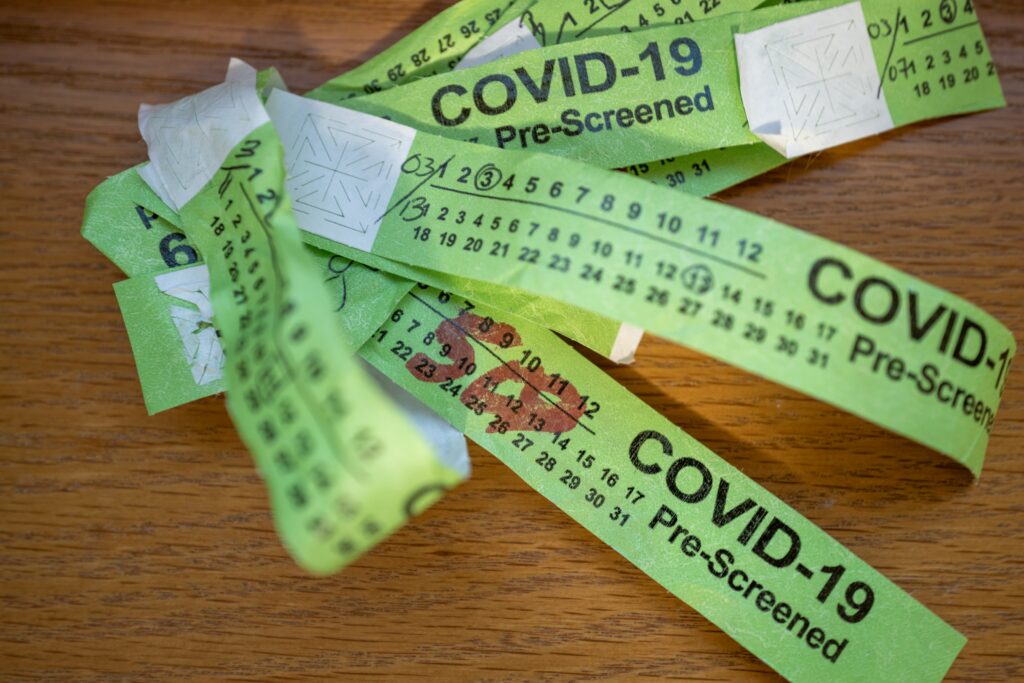

We have been collecting the hospital wristbands, for no particular reason. Looks like they were once used to designate COVID-19 pre-screening. They remain, but not their purpose. Sure the hospital has a few patients with the virus, but the pandemic protocols ended long ago.

I used Leica Q2 to take the Featured Image, which is composed as captured. Vitals, aperture manually set: f/2.8, ISO 100, 1/5 sec, 28mm; 6:54 p.m. PDT. Shot was handheld; I don’t own a tripod.