In May 2010, I wrote about Apple’s market cap passing top-valued Microsoft; it’s only fitting to follow up with an analysis about the unbelievable turnabout that, like the first, marks a changing of technological vanguards. Briefly today, the software and services giant nudged past the stock market’s fruit-logo darling. A few minutes after 1 p.m. EST, the pair’s respective market caps hovered in the $812 billion range, with Microsoft cresting Apple by about $300 million. By the stock market close, a rally for Apple put distance from its rival: $828.64 billion to $817.29 billion, respectively (Bloomberg says $822.9 billion, BTW). Consider this: As recently as October, Apple’s valuation touched $1.1 trillion. But since the company announced arguably record fiscal fourth-quarter earnings on November 1st, investors have punished shares, which currently are down about 21 percent.

Apple has long been a perception stock, even when under the tutelage of CEO Tim Cook company fundamentals deserved recognition. But perhaps Wall Street finally realizes the problem of iPhone accounting for too much of total revenues at a time when smartphone saturation saps sales and Apple pushes up selling prices to retain margins. More significantly: Apple has adopted a policy of fiscal corporate secrecy by stepping away from a longstanding accounting metric. I started writing news stories about the fruit-logo company in late 1999. Every earnings report, Apple disclosed number of units shipped for products contributing significantly to the bottom line. No more. Given current market dynamics, everyone should ask: What is Cook and his leadership team trying to hide?

Fire in Cook’s Kitchen

Apple’s justification for changing reporting—essentially that units don’t matter—is hollow. Among other things, Wall Street analysts use the metric to calculate average selling prices, which being up, incidentally, are numbers the company should want to showcase. Unless, of course, they’re going down. Transparency, or lack of it, means something when one product accounts for so much of sales. That would be 59 percent from iPhone during fiscal fourth quarter, up from 55 percent a year earlier. Dependence is all the more significant as global smartphone sales slow. Shipments fell 6 percent year over year in Q3, according to IDC. Measuring actual sales, a quarter earlier, Huawei snatched the No. 2 spot, behind Samsung, from Apple, according to Gartner.

I ask again: What is Apple trying to hide? As I will explain in a future essay, mistakes in logistical product planning is one answer. The company makes the same blunder as Microsoft did, during the early decline of its dominance: Trying to sell flagship and associated goods like toothpaste, by offering too many kinds with too much overlapping pricing. Seven base Apple smartphone models are available before factoring in storage capacity and other attributes (like color): iPhone 7; iPhone 7 Plus; iPhone 8; iPhone 8 Plus; iPhone XR; iPhone XS; iPhone XS Max. That’s a recipe for pure buyer confusion, while increasing manufacturing and distribution costs. But that’s topic for future elaboration. Suffice to say for today: Consumer confusion at a time when fewer people are buying new smartphones, while presumably increasing cost to make them and raising prices to compensate, isn’t a long-term success strategy.

I can make such assertion with confidence because there is measurable precedent: Microsoft made similar tactical miscalculation with its high-margin profit centers Office and Windows starting in the last decade. Anyone remember the, count `em, nine Windows 8 versions? I sure do. That said, Microsoft’s costs were largely upfront in software development. Apple manufactures things that cost per unit—inventory that must be properly managed, lest there be too many widgets produced and not enough of them sold (like the G4 Cube eighteen years ago).

But I digress. iPhone toothpaste marketing—too many kinds with overlapping benefits—and Apple’s revenue over-reliance on the one product are but reflections of megatrends. Like the PC after the turn of the century, its smartphone successor’s dominance has peaked globally. For Apple, the revenue stream is long-term unsustainable without some dramatic change. More barriers present than opportunities. For example, according to Gartner, Android dominates the global smartphone landscape with 88 percent share; iOS takes leftovers.

Microsoft’s Makeover

Perhaps in Microsoft there is another lesson. The momentary valuation change isn’t just about the stock of one falling. Microsoft’s turnabout today is much more significant than Apple’s tumble. Flash back to fiscal first quarter 2010, when the Office-Windows-Windows Server stack largely accounted for the majority of Microsoft’s $12.92 billion revenue, which with a deferral fell 14 percent year over year. By comparison, during FQ1 2019, which is the most recent, rising revenue (up 19 percent to $29.1 billion) splits relatively evenly across the three major reporting divisions: Productivity and Business Processes ($9.8 billion); Intelligent Cloud ($8.6 billion); Personal Computing ($10.7 billion).

Under CEO Satya Nadella, Microsoft is made over. Product lines are simpler, as is organizational structure. Then there is the risky, but successful, shift to the cloud, where the company extends the Office-Windows-Windows Server stack upwards. The transformation is nothing short of phenomenal, particularly given how badly Microsoft fumbled the smartphone OS market. The company’s apps now support most major operating systems—embraces them, which is a huge departure from the era of favoring Windows above all else. In 2018, Office is a subscription, like other once purchase-only software or software-based products. As such, revenue is more reliable and less dependent on variances in hardware sales or upgrade cycles.

Microsoft’s market valuation rises in part because the business is sounder and well-positioned to capitalize on the contextual cloud computing era. By contrast, like were Office and Windows on PCs, Apple’s fortunes are too tied to personal devices. While services revenue grows—up 17 percent to $9.98 billion in fiscal Q4—contribution is only 15.87 percent of total revenues. Cook touts services during earnings calls, but cloud revenue largely depends on iOS or macOS devices; to reiterate, like Microsoft applications favoring Windows during the PC computing era.

When Apple’s valuation topped Microsoft’s nearly a decade ago, it marked a moment in the transition from PCs to mobile devices. The winds are shifting again, and they will accelerate transition to cloud computing, which already is ubiquitous. As Microsoft’s fortunes rise, Apple’s fall; granted they aren’t interconnected, and perception still is a major and unmeasurable factor affecting the stock market’s fruit-logo darling. But don’t be surprised if there aren’t future dances between the two rivals for the top-valuation trophy. Microsoft’s depth is far greater than Apple’s, particularly when factoring in business market presence. Looking ahead, Apple’s strength to date—end-to-end control—is likely weakness, much as Microsoft’s past, nearly exclusive application support tied to Windows.

Could it be that investors are wising up and putting fundamentals ahead of hype? We shall see.

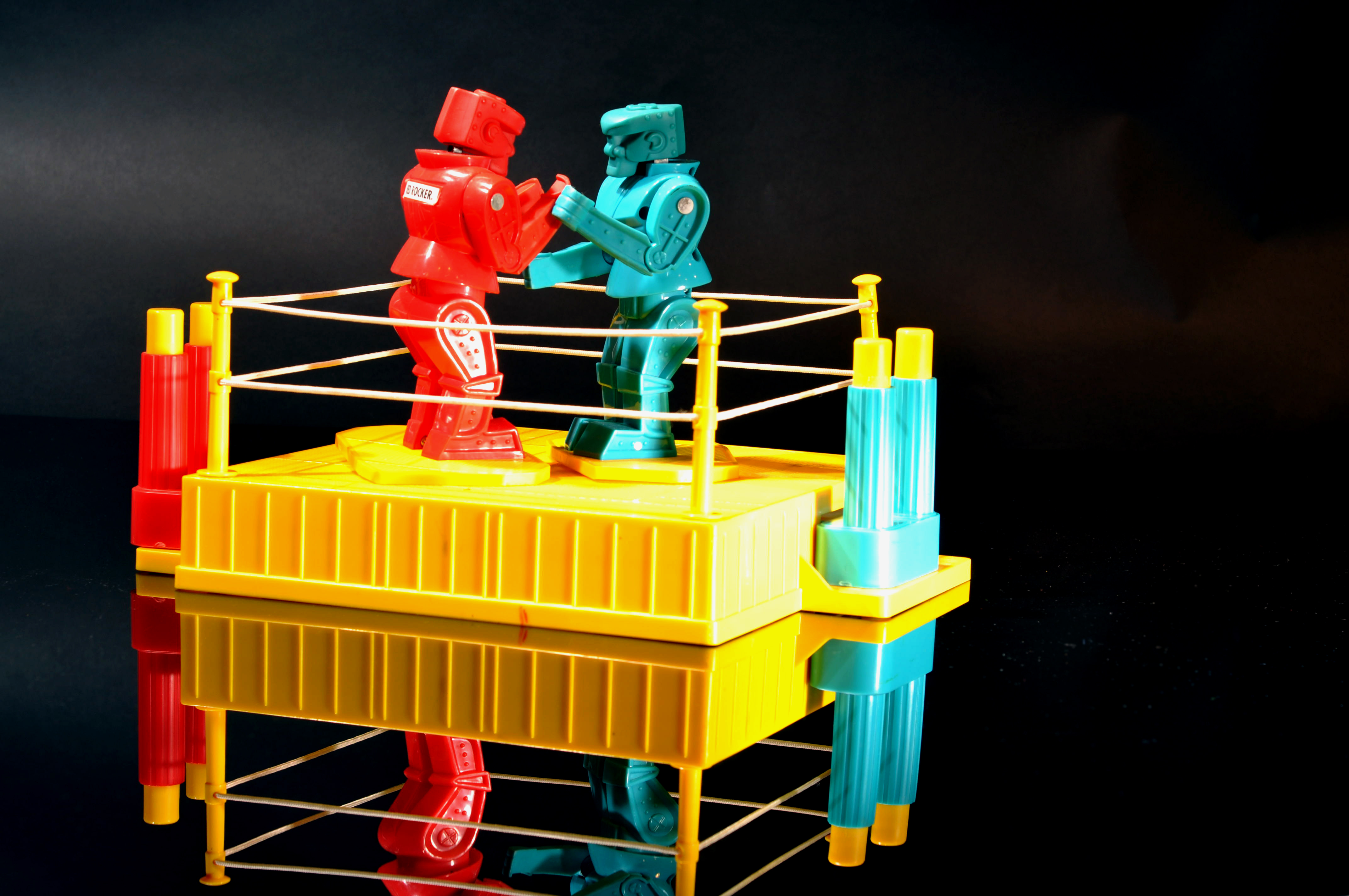

Photo Credit: Ariel Waldman

Editor’s Note: A version of this story appears on BetaNews.