As a science geek, college biology major (decades ago) and pragmatist, I am appalled that any person or company is granted patents over genes. It’s simply unconscionable to grant ownership over laws of nature, which allowance defies centuries of sound legal prudence. If the Obama Administration and 111th Congress want to do some more meaningful health-care reform, abolishing gene patents would be the right place to start.

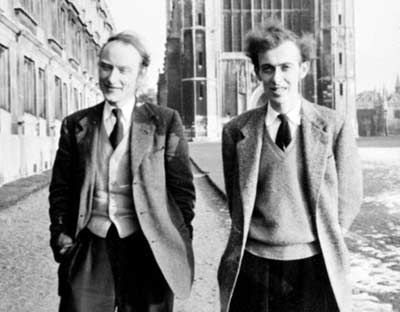

There is something so oddly together about where genes started and where they are today. In February 1953, Francis Crick and James Watson uncovered “the secret of life” when identifying the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid, more widely known as DNA. Their pioneering work later led to the Human Genome Project, which when completed in 2003 identified “the approximately 20,000-25,000 genes in human DNA,” according to official information.

But the business of science changed much over 50 years. On Jan. 31, 2004, I wrote in post “Whatever Happened to the Free Spirit that spawned the Modern Internet?“:

Knowledge comes with a price tag and, worse, a copyright. Only 50 years ago, Francis Crick and James Watson uncovered the structure of DNA. Theirs was a great accomplishment that greatly advanced the study of biology. If Misters Crick and Watson had made their discovery today, they would have needed to secure patents to protect the finding and future profits of those ponying up research funding.

Sadly, these true academics planted seeds which fruit is the the patenting of human genes. Patents essentially grant individuals or businesses a monopoly over a concept, design or process. Other individuals or companies can develop competing concepts, designs or processes, which is good for them and the public good. Genes are creations of nature that, so far as scientists know, cannot be duplicated. There is no competition when someone claims ownership over a natural creation. It’s a sole monopoly that harms the public good, because patent enforcement disrupts research and new marketable products. Proponents of gene patents argue that they facilitate biological research. Michael Crichton strongly disagreed in March 26, 2006 New York Times Op-Ed:

The question of whether basic truths of nature can be owned ought not to be confused with concerns about how we pay for biotech development, whether we will have drugs in the future, and so on. If you invent a new test, you may patent it and sell it for as much as you can, if that’s your goal. Companies can certainly own a test they have invented. But they should not own the disease itself, or the gene that causes the disease, or essential underlying facts about the disease. The distinction is not difficult, even though patent lawyers attempt to blur it.

I had been meaning to write on this topic for more than a year, but chose today because of Genetics in Medicine vol. 12 no. 4 commentary “Putting Patients Before Patents” and story “More Harm than Good? Patenting Genes is Bad for Diagnosis” from April 17th-23rd, 2010 Economist. The current Genetics in Medicine issue presents eight case studies looking at the effects of gene patents on research. Dr. James Evans—MD and PhD—writes:

It is an auspicious time for these studies to be published. The issue of gene patents is at the heart of several pending legal battles, including a case against Myriad Genetics that asserts that genes are not legitimately patentable material and that the enforcement of such patents is unconstitutional.

On March 29, a New York court voided Myriad Genetics patents for BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene sequences related to breast cancer. In his 152-page ruling, US District Judge Robert Sweet laid out the fundamental issue before the court:

Are isolated human genes and the comparison of their sequences patentable? Two complicated areas of science and law are involved: molecular biology and patent law. The task is to seek the governing principles in each and to determine the essential elements of the claimed biological compositions and processes and their relationship to the laws of nature.

Judge Sweet used several Supreme Court and lower-court rulings to establish legal precedents that laws of nature are not patentable. He then tore through Myriad Genetics’ arguments that their genes aren’t really laws of nature because they are changed from those naturally occurring. Judge Sweet makes a clear and concise argument, one that should make biologists proud, about why the DNA is unchanged.

The case, while a milestone, will be litigated for years. So the gene patent problem remains. Dr. Evans writes:

When rights to the human genome are fragmented to the point that thousands of genes are ‘owned’ by myriad parties (pun intended), how will we hack our way through the resultant thicket to facilitate the application of multiplex genotyping, multiplex sequencing, and whole genome sequencing?…These harms are most clearly seen when an exclusive (or no) license is issued by a patent holder, resulting in only a single laboratory that is allowed to perform a given test.

Resonating with Michael Crichton, Dr. Evans writes: “The case studies also suggest that gene patents and the lure of exclusivity are not needed for the development and wide availability of genetic diagnostic tests.” He goes on to advocate changes in policy.

He’s not alone. In early February, the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health and Society issued a compelling report raising concerns about genetic patents and advocating some policy changes. Perhaps most compelling from a health-care policy perspective is the effect of these patents on the aforementioned tests.

SACGHS notes case studies raise “concerns about the quality of tests provided by sole providers…The existence of multiple laboratories offering the same test can facilitate confirmatory testing in the clinical context, which is perhaps the best way of allaying concerns about the quality or accuracy of a particular provider’s test.” More:

The Committee found that a near perfect storm is developing at the confluence of clinical practice and patent law. The cost of genetic analysis is decreasing dramatically, while knowledge about the genetic foundations for health, illness, and responsiveness to medicine is growing exponentially…

Trends in patent law appear, however, to pose serious obstacles to the promise of these developments. Patenting has moved upstream; instead of covering only commercial products, patents can now control foundational research discoveries, claiming the purified form of genes. Fragmented ownership of these patents on genes by multiple competing entities substantially threatens clinical and research use.

Gene patent reform is consistent with many of the philosophical and constitutional objectives behind Obamacare. It’s time for Congress to enact legislation that applies sound policy to gene patents and enforces the precept that laws of nature aren’t patentable.

Photo Credits: DNA origami by Dullhunk; Francis-Crick from public domain