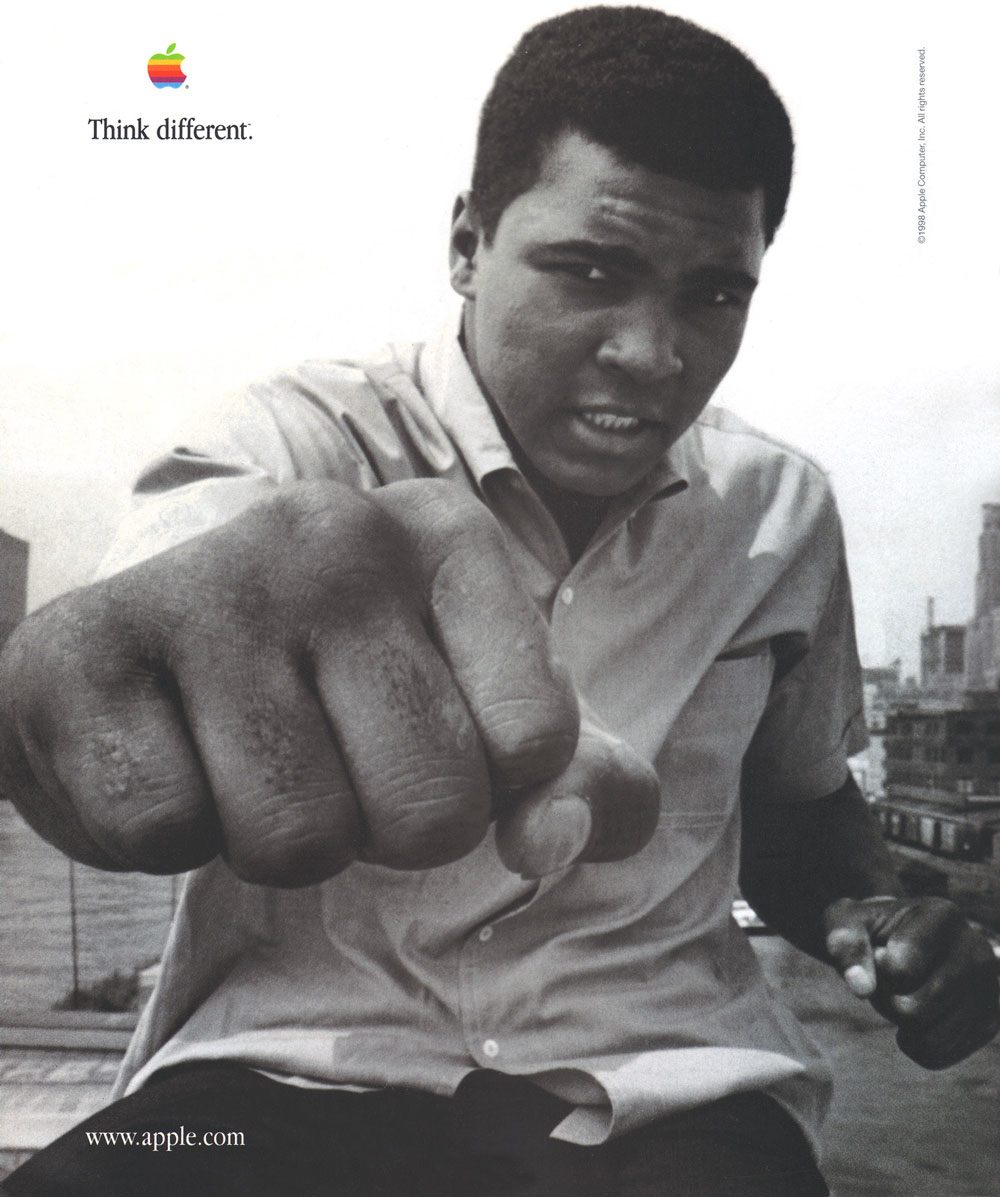

Simply put: Apple doesn’t play by the rules. It reinvents them.

The March 11, 2009, The New Yorker magazine features story, “How David Beats Goliath.” Writer Malcolm Gladwell could easily have written about Apple; his examples are 12-year-old girls basketball and T.E. Lawrence.

Malcolm tells how obvious losers can be winners if they don’t play by the rules:

David’s victory over Goliath, in the Biblical account, is held to be an anomaly. It was not. Davids win all the time. The political scientist Ivan Arreguín-Toft recently looked at every war fought in the past two hundred years between strong and weak combatants. The Goliaths, he found, won in 71.5 per cent of the cases. That is a remarkable fact…

In the Biblical story of David and Goliath, David initially put on a coat of mail and a brass helmet and girded himself with a sword: he prepared to wage a conventional battle of swords against Goliath. But then he stopped…and picked up those five smooth stones. What happened, Arreguín-Toft wondered, when the underdogs likewise acknowledged their weakness and chose an unconventional strategy? He went back and re-analyzed his data. In those cases, David’s winning percentage went from 28.5 to 63.6. When underdogs choose not to play by Goliath’s rules, they win, Arreguín-Toft concluded, ‘even when everything we think we know about power says they shouldn’t.‘

(For a further explanation and even application of the findings, I recommend two commentaries written by Ivan Arreguín-Toft: “How a superpower can end up losing to the little guys” and “Why victory became defeat in Iraq.” By the way, these citations aren’t meant as reflecting my personal views about wars. These happen to be the topics Ivan has applied his findings.)

Steve Jobs as David

Apple isn’t a team player. Since the company’s founding more than three decades ago, Apple has set its own rules, particularly under the two chief executive tenures of cofounder Steve Jobs.

The examples of Apple’s rule-changing behavior are simply too numerous to recount. So I’ll start with a few around the 1984 launch of Macintosh:

- While Compaq and other clone upstarts sought to imitate the IBM PC, Apple defied it. The Macintosh’s graphical user interface, mouse and other features defied convention.

- The “1984” commercial launching Macintosh aired only once, bucking traditional marketing approach of repeated airings to build brand and product awareness.

- Apple bought out every single ad space in the Newsweek 1984 election issue—39 pages.

- Macintosh came bundled with Apple applications MacPaint and MacWrite.

Apple’s business was at its worst, the company closest to expiration, during the early 1990s, when the company played more by rules established by Microsoft. Apple had put on Goliath’s mail and brandished his sword. For example, Apple embraced clones, allowing third parties to release their own hardware running Mac OS. The seemingly sensible strategy was anything but. Apple’s attempts to play by DOS/Windows PC rules put the company at grave competitive disadvantage. Steve Jobs’ late-1996 return to Apple and ascension to interim CEO in 1997 set forth dramatic changes in the company’s business strategy. Among Steve’s first actions: The end of Mac cloning. Only Apple would make and sell Macs.

There are so many examples of Apple changing the rules, it’s hard to find ways the company played by Microsoft’s—and other Goliath’s—rules. Some examples:

- Streamlined product SKUs, from 1997 to present: Following Steve’s second coming, Apple reduced the number of products in each family. Example: Today there are three Mac notebook families, with three models in each of the MacBook and MacBook Pro lines and two for MacBook Air. Popular convention is to offer more product families and SKUs. The counter-culture approach lets Apple streamline manufacturing and distribution while maximizing margins.

- Bondi Blue iMac, released 1998: Some Windows PC OEMs offered all-in-one designs, but none like Apple, which dumped all the legacy ports for USB and FireWire. Hundreds of translucent products followed the design trend established by iMac.

- Apple Store, first opened in 2001: Apple moved into retail during a recession and while Gateway prepared to shutter, and later closed, hundreds of store. Everything about Apple Store, from design to retail staff training and more, defied computer retail convention. Genius Bar was a genius concept for servicing customers and endearing good feelings about Apple products. Goliaths Circuit City and CompUSA later liquidated. Apple Store is a vibrant retailer.

- iPod, launched in 2001: Apple redefined the nascent MP3 player market with the click wheel and hard-disk storage. Then Apple reinvented the device with iPod nano and again with iPod touch. Companies more typically seek to preserve the status quo they create. Apple has chosen to instead repeatedly reinvent iPod.

- iPhone, launched in 2007: Like David, Apple played to its strengths, such as software and industrial design, rather than play by rules established by handset carrier and manufacturing Goliaths. Examples include use of capacitive instead of resistive touchscreen, multitouch user interface, synchronization and control of software, software updates and services (rather than letting the carrier control them).

- Recessionary pricing, now: Apple pricing has long defied convention. The company prices high, choosing not to compete with Windows PCs in the sub $500 market. The approach preserves the brand’s value and margins. No time has Apple’s higher pricing been more obvious than during the current recession. So far, Apple’s rule-changing approach defies low-pricing logic. Price cuts are inevitable, I believe. But not now and certainly not massively.

Once David, Microsoft is Goliath

At one time Microsoft changed the rules, too, when David to the IBM Goliath. For example:

- Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates admonished early developers in 1976 “An Open Letter to Software Hobbyists. The convention had been to share code, which he called stealing.

- Bill and other cofounder Paul Allen licensed what would later be called MS-DOS to IBM in 1981, rather than selling the software. The approach broke the end-to-end hardware/software model and later flourished a robust IBM PC-clone market.

- Microsoft’s approach to partnering, particularly software developers and resellers, put more money in others’ pockets. In the IBM model, money flowed up. By contrast, Microsoft shared the wealth.

There are many other examples how Microsoft defied convention over the years, how the company changed the rules. No longer. Microsoft seeks to preserve the status quo. For example, top perennial design principle for Windows is backward compatibility. It’s the preservation of the past way of doing things.

Similarly, Microsoft’s approach to enterprise computing is in many ways stifling rather than empowering. I’ll elucidate some time in the future. For now, suffice to say that, for example, Microsoft strategies around Business Intelligence or Unified Communications aren’t what they are claimed to be. These strategies extend the business process already in place—they preserve the status quo, whether the customers’ or Microsoft’s existing products. Outside-the-box, rule-changing before would lead to revolutionary processes, and with them new growth for all parties.

Status quo thinking—rules established by Goliath—prevent Microsoft from being competitive and disruptive like Apple. But there are pockets of true innovation, of Davids changing the rules. Office 2007 is excellent example. Not only did Microsoft revolutionize the user interface, there was no fall-back option. Businesses couldn’t turn on the classic Office UI. Microsoft moved customers forward by defying some of its long established rules about backward compatibility. Guerrilla groups have produced some truly exciting new products, like WorldWide Telescope and—if it really works as promised—Azure Services Platform.

But Goliath thinking is so pervasive, Microsoft fails where it shouldn’t. Microsoft will never beat Google in search, because the software giant plays by the search and information giant’s rules. Microsoft must change the rules of the engagement, leveraging its strengths against Goliath Google. Malcom writes in The New Yorker:

David, let’s not forget, was a shepherd. He came at Goliath with a slingshot and staff because those were the tools of his trade. He didn’t know that duels with Philistines were supposed to proceed formally, with the crossing of swords…He brought a shepherd’s rules to the battlefield.

Microsoft must leverage its strengths, battling Google in an unexpected way. But the how must be topic of a future post. By contrast, Apple has consistently competed, at least under Steve Jobs’ leadership, in ways that emphasize its strengths rather than complying with rules set by others. Should Steve not return from his medical leave next month, Apple’s challenge will be to keep up this David thinking.

Convention is Goliath’s Game

Apple’s rule changing is remarkable, given how much ridicule Goliaths have given.”The price that the outsider pays for being so heedless of custom is, of course, the disapproval of the insider,” Malcom writes. The disapproval is another Goliath tactic, of demeaning David for violating business cultural mores. Apple has long defied the criticism, which has put Goliath Microsoft on the defensive. Apple’s “Switchers” and “Get a Mac” marketing campaigns turned the attack and ridicule back to Microsoft. Who blinked first? Microsoft did with its “I’m a PC” Mac counter-marketing campaign.

Microsoft’s mightiest weapon against Apple is marketshare measurement, although a newer tactic ridicules Apple product pricing (The so-called “Apple Tax”). Microsoft has long touted Windows PCs’ overwhelming marketshare lead over Macs. Gartner’s most recent PC shipment data put Apple’s US marketshare at 7.4 percent, which, by the way, declined over three quarters.

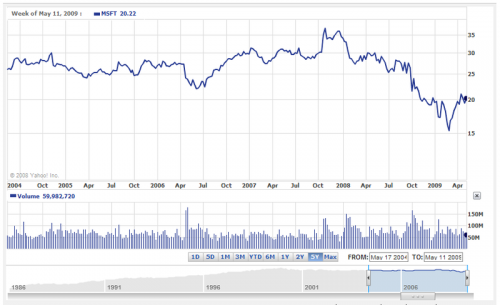

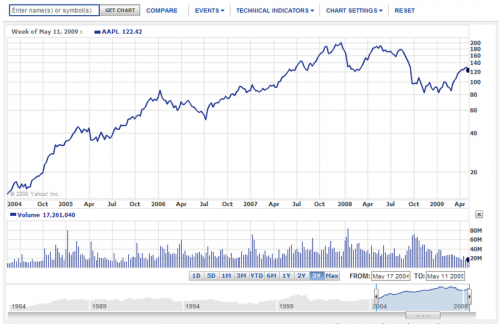

But marketshare is not the measure of success. For public companies, return of profits to shareholders is the measure of success. During first calendar quarter Microsoft posted net income of $2.98 billion, or 33 cents a share. Apple delivered $1.21 billion net income, or $1.33 a share. A quarter earlier, Microsoft reported $4.17 billion net income and 47 cents a share; Apple net income of $1.61 billion and $1.76 a share.

The two charts above, from Yahoo Finance, show Apple and Microsoft shares over five years through May 14, 2009. Which company’s shares would you rather own? Which company’s strategy looks better to you based on stock performance—Goliath and the status quo or David the upstart?

[An updated version of this analysis posted to Betanews on Dec. 9, 2009.]