When I worked as an analyst for Jupiter Research a decade ago, the editorial philosophy was “data-driven analysis”. But sometimes single stories—one or a few individuals—define a trend. That’s my renewed feeling today meeting Tim in the alley behind our apartment.

I measure San Diego’s economy, and in some respects that of America, by the people who dumpster dive our alley. We moved to the city seven years ago yesterday and were taken aback by the number of people who pull redeemable bottles and cans from recycle and trash bins. But the collectors’ character changed in 2009, following the financial crisis of late 2008. No longer did we see just clearly weather-worn homeless, but paler and better-dressed folks not long laid off from office jobs. Professionals.

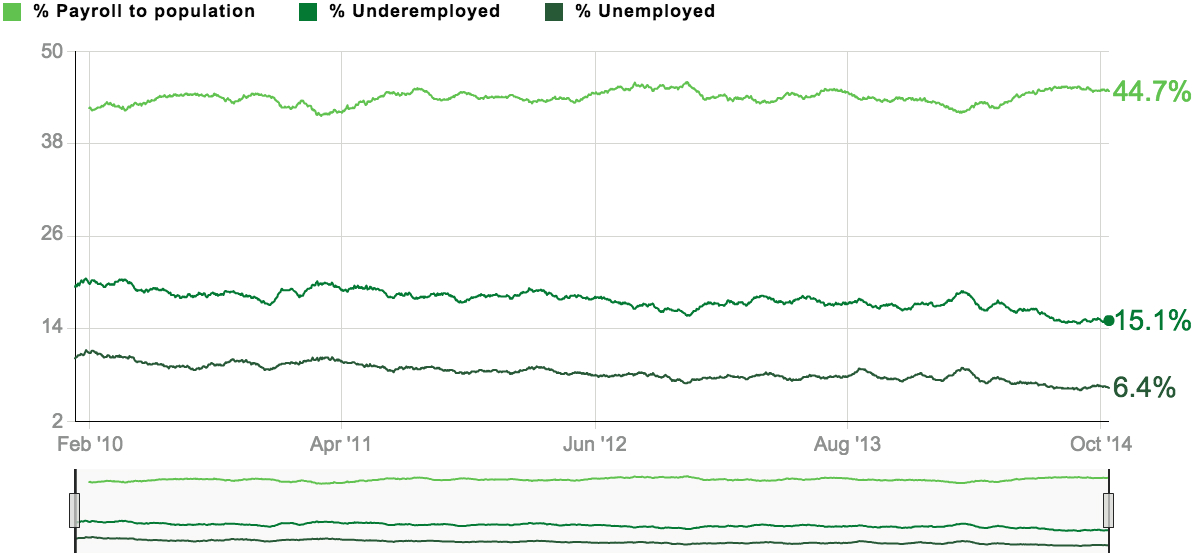

We see fewer dumpster divers of this ilk in 2014, which says something about the validity of that 5.9 percent national unemployment rate released two weeks ago. But the stats don’t reveal the number of underemployed, which I define as people seeking full-time work but who only can find part-time jobs, or those who have given up looking. According the Gallup, yesterday, Oct. 15, 2014, the underemployment rate was 15.1 percent, compared to an unemployment rate of 6.4 percent. The difference disturbs.

More broadly, the number of underemployed is declining, but erratically, depending on demographic, with recent college graduates and older workers among the most affected. According to the U.S. Census Bureau report “Income and Poverty in the United States: 2013“, released in September 2014: “An estimated 72.7 percent of working men with earnings and 60.5 percent of working women with earnings worked full time, year round in 2013, both percentages higher than the 2012 estimates of 71.1 percent and 59.4 percent, respectively”.

That’s the good news. The bad: “The number of full-time, year-round workers in 2013 was less than the 2007 peak of 108.6 million”. Some of those jobs disappeared. Many others reflect employers replacing full-time positions with several part-time ones. Because of full-time benefits like health insurance, paying several part-timers for the same job costs employers less.

Man in the Alley

Tim is underemployed. I didn’t ask his last name and wanted to take his photo. But, damn, I left my phone in the apartment, and he departed too soon for me to fetch the device. I had gone out to grab something from our shared garage facing the alley, where Tim sat with two luggage bags and one box pushed on a flimsy, aluminum hand cart. I assumed that he stopped to rest from collecting cans, which I offered him from our stash in the garage.

Bottle and can collectors work hard, and they earn so little compensation for the amount of time invested. California redeems bottles or cans for a nickel a piece; some larger ones are worth a dime. That’s about 400 cans to get $20. We see people with pushcarts, bicycles, and even wheelchairs carrying three, four, five or more large garbage bags full of recyclables. They’re not lazy. This is how they live, how they survive.

Tim wasn’t collecting. The 53 year-old Californian packed laundry, not cans, and he waited for his 60 year-old girlfriend to bring her dirty clothes. One of 13 children, this middle-aged man looks homeless. His skin is so dark from the sun, I couldn’t discern his race. But he doesn’t live on the streets—at least not now. He flops in a utility shed, with toilet facilities, down the alley. He praised his young landlord.

“I would do anything”, Tim told me today about working. He has a new job mopping floors, and his girlfriend is recently employed, too. Both people looked long, and he described the difficulties of being older and getting hired. He didn’t say “age discrimination” but inferred it. In the nine years since being laid off from his professional job, Tim has worked some odd ones, including butcher for a local grocery.

By measure of employment, Tim contributes to that 5.9-percent statistic. But his inability to find satisfying, full-time work puts him in the other category, too. Researcher/consultancy PayScale describes the current job market as an “underemployment crisis“. The measure I use—only being able to find one or more part-time jobs, if any—isn’t the only definition. In conducting consumer surveys, PayScale identifies another, which shouldn’t be ignored:

What can we learn from this study? The primary reason that most workers feel underemployed, in every occupation on our list, is not making as much money as they think they should. Of course, feeling underpaid and being underpaid are two different things: while 80 percent of those who felt underemployed claimed being underpaid as the reason, only 45 percent of those individuals actually earn less than employers typically pay for candidates with similar backgrounds, skills, and experience.

Tim feels underpaid, because he is. Before being laid off in 2005, he earned $44 per hour. Many workers displaced since the econolypse’s start, late last decade, are similarly distressed.

Changing Workforce

Have you ever wondered why there is such sudden, orchestrated effort to raise the minimum wage to $15, now, after staying so long below $10? Underemployed are the answer. People who feel underpaid, because they can’t earn enough from a single job, now depend on the kind of service-oriented jobs once mostly filled by teenagers. Like, McDonald’s!

The U.S. Department of Labor Statistics provides a state-by-state minimum wage guide. Here in California, it’s $9, compared to $7.50 back home in Maine. Up North in San Francisco, next month, voters will decide whether to raise the minimum wage from $10.74 to $15. However, the Insight Center for Community Economic Development claims that’s not high enough. To meet basic housing costs ($1,504) and other essentials, a single adult without children would need to earn $15.66 per hour.

The organization’s Self-Sufficiency Standard Calculator provides detailed insight. For example, in San Francisco County, a family of two adults and children 4 and 8 years-old need to earn $18.42 an hour per adult. Thirty-eight percent of households with children don’t meet the self-sufficiency standard, which is minimum monthly household income of $6,591.

Here in San Diego, the necessary hourly wage is less—$16.91 and monthly household income of $5,949. However, 50.7 percent of households with children do not meet the self-sufficiency standard.

Drama Enough for Television

MTV series “Underemployed” brings the term to popular culture, illuminating the job hardships facing not the oldest but youngest members of the workforce. What good is that college degree when you can’t get a job, all while carrying tens of thousands of dollars in student loan debt?

Debt is the problem. No one graduating college should carry massive debt while trying to start a career. According to the Institute for College Access and Success Project on Student Debt, 71 percent of graduating college seniors have student loan obligations, for an average $29,400 per borrower. The organization provides state-by-state data. For all California, the number is $20,269, with 52 percent of graduates owing for loans.. Locally, at San Diego State University, 44 percent of students have loan debt, or $17,600 per graduate. Data is for 2012.

Indebted graduates join a large number of Americans burdened by the remnants of the housing bubble. I am a long-standing critic of the bank bailout and firmly believe that the institutions should not have been artificially propped, because economics follows patterns similar to natural law.

When the old forest blocks sunlight for new growth, dry leaves build up to a point that a lightning strike sets the forest to blaze. New growth follows the forest fire. Similarly, we all would have severely suffered from banks’ collapse, but for many reasons—technological advances among them—new institutions would have risen from the crisis. Instead, the propped-up old vanguard and the corrupt culture behind it remain, and many Americans are stuck in debt that bank collapses would have erased. Debt created by a false, bubble economy that should have been naturally purged rather than artificially maintained.

Debtor graduates need to work somewhere. According to PayScale, if you want a good job out of college, your degree better be in engineering or mathematics. Among the highest-earning degrees, engineering captures 13 of the top-20 spots. Five of the other seven require strong math skills.

Funny thing, Tim says he was an engineer working for Boeing, with responsibilities related to the landing gear—I presume on an assembly line. At the least, he was a highly-paid skilled laborer with earnings of no less than $91,520 a year, assuming 40-hour work week, now reduced to mopping floors for minimum wage—and he’s grateful for just that.

I wonder what life stories Tim will share should some recent college graduate, unable to find work in his or her chosen field, mop alongside him. Tim’s underemployed future isn’t totally dim. He looks forward to a Boeing pension starting at age 65. What will the indebted, underemployed college grad have to look forward in another 12 years? You tell me.

Photo Credit: David Shankbone

Editor’s Note: Tim isn’t his real name.