Not since (what was then) SciFi Channel televised the Battlestar Galactica miniseries in 2003 has science fiction storytelling been so good as Ascension, which aired last week. BSG changed the tone and tenure of speculative drama, that felt altogether more real in the aftermath of the 9-11 terrorist attacks on U.S. soil. Later watchers won’t feel the same about the miniseries or full seasons that followed. They’re beret of the shared context that amplified the emotional content.

Ascension’s showrunners smartly seek something similar, but playing reminiscent emotions rather than anger or fear. For aging Baby Boomers, and even their descendants, Ascension is a time tunnel to the early 1960s, perfectly preserved 51 years later. Pop! Let’s look inside the time capsule! i09 calls Ascension “Mad Men in Space”, and there’s something to that allusion. But unlike later Mad Men seasons, which carried the characters forward into the decade’s crises and conflicts, Ascension harkens a golden era of innocence before Civil Rights, Vietnam, war protests, hippies, political assassinations, or even the Beatles.

In July, my household disconnected TV service (e.g., cut the cord), going all streaming. That means no Syfy here. But Ascension’s strange premise, an interstellar mission launched in the early 1960s, even before humankind reached the moon, intrigued. So I paid iTunes $7.99 for the full miniseries, and watched each of the three segments one-day after airing. I purposely, and it turns out wisely, did not preview the trailer and featurettes, or read reviews.

A moment to pause: If you haven’t watched Ascension, I highly recommend that you read no further. Because you should watch the miniseries, and the spoilers that follow will ruin it for you. Last warning: Stop now while you still can. To anyone else: Read! Read!

Defying Gravity

TV science fiction storytelling hasn’t been this strange since Lost aired a decade ago. Ascension plot twists are deliberate gotcha cliffhangers that leave viewers wondering “What the frak is that?” Little in Ascension is what it appears to be. But Lost lacked cohesion and fluidity; plot twists disjointed the storyline and in later seasons twisted it. By contrast, Ascension is cohesive, consistent, and careening—shooting off in unexpected directions, like the aftermath of an interstellar collision but always within bounds of gravity.

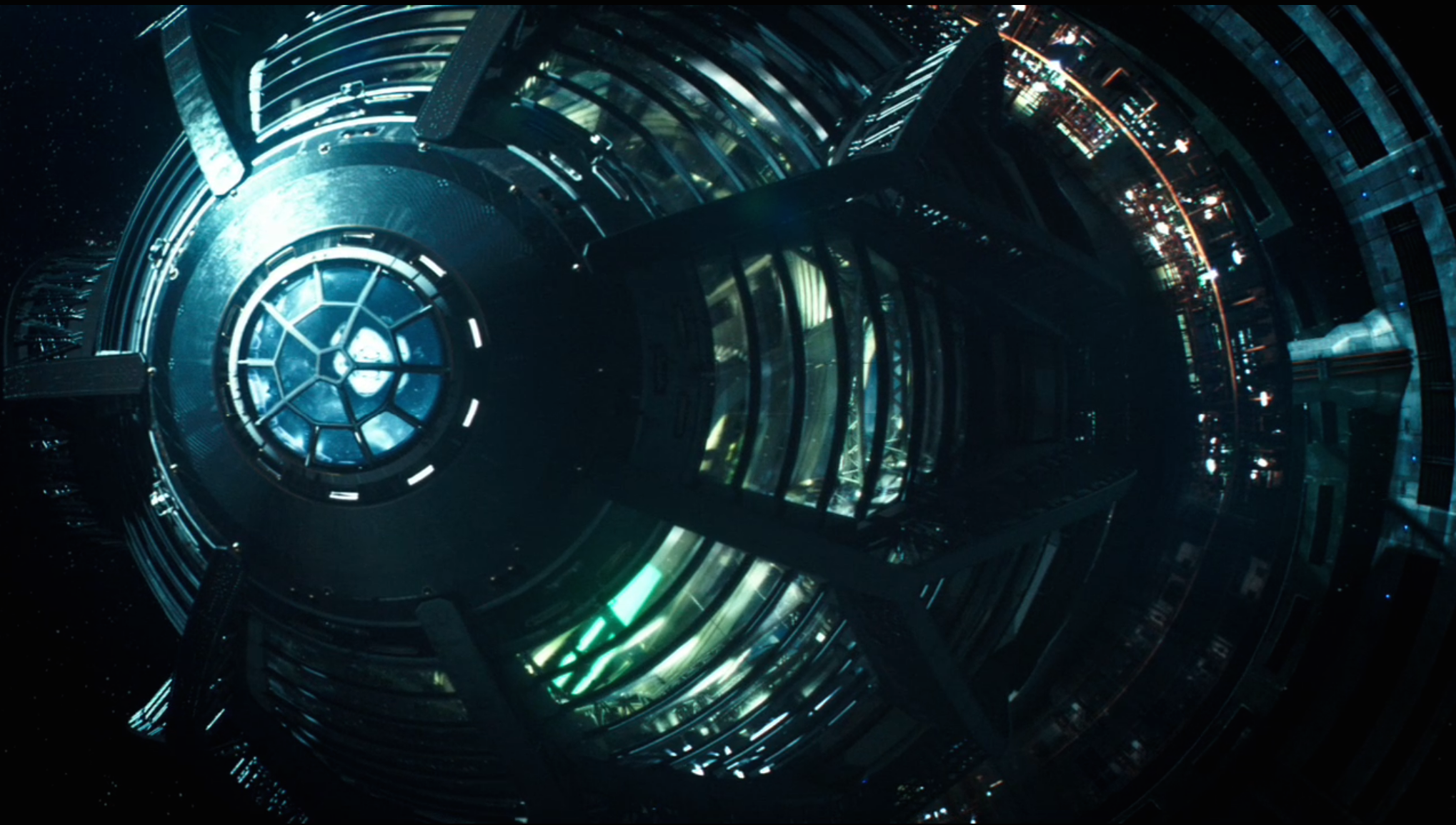

I left the first night’s viewing disappointed. Before watching, I thought that perhaps Syfy cleverly presented an alternative reality where the United States really had launched a 100-year mission to Proxima Centauri, a planetary system that most Americans can’t even see in this hemisphere. Instead, the ship is here on earth and part of a grand sociological experiment. A fraud. The USS Ascension is a rocket to nowhere, and that realization was my descension to disappointment.

But I had to wonder what the showrunners planned for two more nights of what had been until then superb storytelling. The sets are lavish, time period (past and present) believable, characters compelling, and the drama intoxicating. Besides, I already paid eight bucks.

The second segment shone brighter than the approaching Centauri system, as viewers got a glimpse of real life inside the 1960s bubble and how it changed in response to the necessities of confinement, cultural baggage carried forward to the original crew’s descendants, and human foibles that turn even “heroes” into villains.

The third installment delivered some of best storytelling I’ve seen on television in years—and not on Syfy since Battlestar Galactica ended. You can’t count the plot twists there are so many, ending with character Harris Enzmann’s startling proclamation “You’re wrong. They are heroes, and they’re going to space”. Seeing what transpired, I believe him, and long to see an Ascension TV series that gets them there.

Because: Ascension is rich with foreshadowing tells that shouldn’t be ignored. Before the big reveal at Day 1’s end, I wondered why there was gravity on the spaceship. That tick in science, what appeared to be Syfy taking liberties, meant something else. Another example: During the final episode, Enzmann, played by Gil Bellows, off-handedly says one thing that in later context could mean something else: USS Ascension “was designed to take the direct impact of an asteroid”. The ship is spaceworthy. Maybe they really are, in the event of a future full TV series, “going to space”.

Cultural Revolution

Yesterday, my 20 year-old daughter texted: “Out of the `60s, `70s, and `80s which was your favorite?” I replied: “The `80s. I was 21 in 1980. The 20s are your best years. Why do you ask?” Her answer: “Been listening to lots of Beatles”—and I should add she just finished a sociology course on the 1960s.

As Boomers age, and look back to their youth—many of them in their twenties during the 1960s—they will, as we all do, put on rose-colored glasses. What was looks better now then it did then. Meanwhile, watching my college student child and the Millennial generation, which size is larger than the Boomers, I see the turning of the cultural clock. What was is again. Trends in design, dress, music, and popular culture pick from the 1960s fabric and weave new tapestry.

Mad Men in space will appeal to a much broader audience than the late-50s and older set. The majority of Ascension characters are Millennial and GenXer age; easy to identify with. Outside the bubble, in the real 2014, the largest chunk of Millennials are in their twenties, same as the hump of Boomers were during the 1960s. Ascension storyrunners aren’t stupid. They identify potentially broad audience spanning generations.

Where the brains behind Ascension also show brilliance: Many of the gadgets used on ship were designed there, and they are just recognizable enough with, for example, tablets and video devices today to be familiar to younger viewers while evoking enough 1960s-era science fiction film and TV design to grab Boomers.

There are so many ways Ascension’s story could unfold. During the miniseries, in that 1960s largely preserved, the ship’s crew members exists in a time of innocence, believing they are heroes and humankind’s last hope. In the real history, the latter 1960s reflect reactions to innocence shattered. Similarly, Ascension could be, and what a story to be told.

If the USS Ascension is a grand sociological experiment or even a relic for the stars, so are we. The series has potential to comment on past and present, and capture the kind of emotional context that made Battlestar Galactica tick. The series sometimes made the villain Cylons more sympathetic characters, because our humanity was so darkly portrayed.

BSG also set atop cultural and technological revolution that changed how we consume television programs. There was no Hulu, Netflix streaming, or YouTube when Battlestar Galactica aired as a miniseries in December 2003 or when season one followed—October 2004 in the United Kingdom and January 2005 in the United States and Canada.

But fans outside the UK couldn’t wait. Episodes appeared on BitTorrent as soon as they aired. But rampant piracy benefitted rather than hurt viewership. In a two-part May 2005 story for MindJack, Mark Pesce explains:

While you might assume the SciFi Channel saw a significant drop-off in viewership as a result of this piracy, it appears to have had the reverse effect: the series is so good that the few tens of thousands of people who watched downloaded versions told their friends to tune in on January 14th, and see for themselves. From its premiere, Battlestar Galactica has been the most popular program ever to air on the SciFi Channel, and its audiences have only grown throughout the first series. Piracy made it possible for ‘word-of-mouth’ to spread about Battlestar Galactica.

NBC Universal and Syfy responded by streaming online select Battlestar Galactica episodes by summer 2005, a few months before Apple starting selling television programs via iTunes. Full-episode TV streaming was pretty novel in early 2005. Perhaps not coincidentally, NBC Universal was the second network to sell TV shows via iTunes and later cofounded Hulu, which opened for public streaming in March 2008.

Ascension’s storytelling is so good; showrunner’s sense so astute about what appeals to the two largest generations ever; the miniseries’ sets, costumes, and overall design ethic so appealing, I wonder what cultural revolution a full series might lead. Only Syfy can answer that.

Editor’s Note: A version of this story appears on Medium.