Growing up in Northern Maine, a white wonderland in more ways than just snow, doesn’t seem like the best place for exposure to other races, or even cultures. But, my hometown Caribou also was where many kids from “the base”, as in Loring over in Limestone, went to school.

My best buds growing up tended be a different color from me, like the Chung brothers, Davis and Winchell. Not that I noticed. I was colorblind to skin. I remember learning about slavery, civil rights, and racism in eighth grade, a concept that made no sense to me.

Last week, I blogged about generations. One thing I did get from the Baby Boomers, this sense that certain attitudes, like judging people by their skin color, was an old-fashioned attitude belonging to the older generation. Surprised was I when in eleventh grade over lunch one day another friend (this one white) started in about blacks (he used a different word I won’t use here). It was a shocking affront to my naiveté that racism was an older folks problem.

Still, this naiveté carried over into my 20s. During the summer of 1984, while in Chapel Hill, N.C., I watched the film “From Montgomery to Memphis“. Growing up in my white wonderland, I had not understood about segregation. First, the shock about black and white buses, then black and white waiting rooms at the bus station, or the black and white bathrooms. But the blow to the solar plexus, the epitome of shame about my race: Separate water fountains. My fourth grader learned about some of these things last week, which she and I discussed over several evenings.

A year later, I moved to predominately black Washington, D.C. for work. I’ve called the Washington area home since, despite some college years in Minnesota and 18 months back in Maine during 1995-96. You don’t grow up white and male and suddenly have a feeling for what it’s like to be a minority, no matter how diverse your friends or the area that you live. But you can try to be a friend to everyone.

That 1995-96 hiatus is worth noting. Soon after my daughter was born, I had a chance to take an editors job running a small cultural magazine in my hometown. My wife and I saw getting away from the crime and congestion to be a good thing. But 18 months later, the isolation (we’re talking a three-hour drive to major city Bangor and its 40,000-plus population) made the crime and congestion look pretty appealing.

Besides, Northern Maine was whiter than I remembered. The air force base had closed down, taking with it much of the cultural and ethnic diversity. We both wanted our daughter to grow up with diversity, and Caribou was the wrong place for that. In January 1997, we returned to Washington. Her elementary school is 50 percent white, which is a tad too much for me. If we lived a few blocks over, she would have attended the stuffy 97-percent white public school in our town, which wouldn’t have been acceptable.

Last night, my wife and I talked about Martin Luther King Jr. over dinner. We both regard him as the greatest American of the last century. Maybe because of the Iowa primary coming tomorrow and all the talk of elections, I stepped back and looked at Rev. King’s murder differently. I thought about political assassinations, meaning the two Kennedy brothers, and much more.

The Baby Boomers like to rabble on about the decade of love—the Beatles, peace marches, and free love. But that decade probably ranks as the most violent in American history since the Civil War a hundred years earlier. Three notable assassinations, including the American President; the brutality leading up to the civil rights movement and beyond it; race riots; and, of course, the Vietnam War. So much for love and peace, baby.

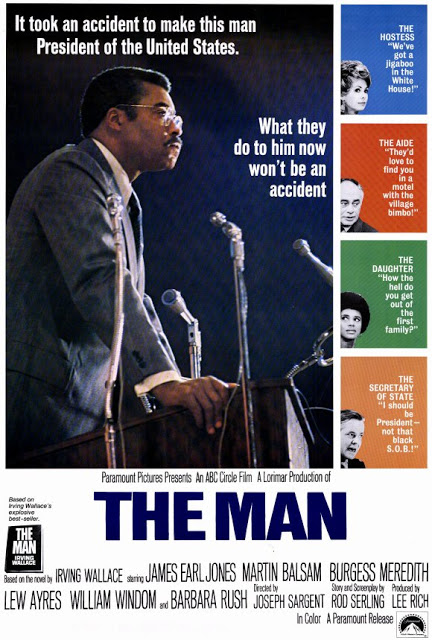

I know that Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday was last week, but we celebrate in holiday today. Happy birthday Dr. King. We need more leaders like you. I look forward to the day when the United States can show its true colors by putting a black man or woman in the White House as president (For a look at that possible future, check out the 1972 movie, “The Man” or any episode of Fox TV show “24“). That some of President Bush’s closest advisors are black is a step forward, but not far enough.