“She talked” is how our daughter’s nurse greeted me today. That statement upfront is so I don’t bury the lede. But behind it are several tumultuous days of disappointment and progress.

Consider this the third installment about our adult child, who suffered oxygen-deprivation following an incident that receives no explanation for now. “Our Family Emergency Revealed” and “From Intubation to Extubation” are parts one and two, respectively. Because my Facebook is deactivated (since July 2019), this post means to update relatives and any one else interested in following the saga.

On March 15, 2023, after spending 13 days in the Intensive Care Unit, our daughter was transferred to a regular room, which she shared with a much older woman, and placed by the window with lovely view of trees. But she brought a small problem along. On March 10, when still attached to a ventilator, she vomited, aspirating some debris into her left lung, which partially collapsed.

On March 16, nurses and respiratory specialists stormed the room every couple of hours. Chest X-ray and beaucoup tests were required. Our girl had developed pneumonia in the left lung. Being bed-ridden still and having difficulty coughing up mucous and other debris made respiratory treatments difficult.

St. Patrick’s Day morning, a nurse called early to inform me that our daughter had been moved back to the ICU. The attending physician also rang not long later. The left lung showed all white on the X-ray and had collapsed. She required massively pushed volume of oxygen, continued antibiotics, and specialized treatments to try and shake loose the gunk filling up the lung.

Under normal circumstances, the doctor would have ordered a treatment that in simplest terms would kind of vacuum out the muck. But doing so would require administering anesthesia. The typical person would recover about two hours later. But my daughter’s tenuous mental progress would be set back days, if not longer.

I sat with her most of the day as she slept and responded little to any stimulus. At times, her tongue hung out of her mouth, and I really wondered if she truly was gone and destined to live out her remaining days (gasp, years) on life support.

Days earlier, the neurologist following her case explained that he ordered the neuron-specific enolase test after she arrived at the hospital, because of cardiac arrest that occurred in the ambulance. Values of 33 ng/mL or above generally indicate a “poor prognosis”, he said. Optimal is 12 ng/mL or lower. Our daughter’s values came back as 17 ng/mL and 19 ng/mL. Combined with a MRI showing strokes on both sides of the brain, the extent of recovery—and how much—would likely be measured in months. Meaning: No one could predict. Unsaid: She showed no interest in food or much else after being taken off the ventilator.

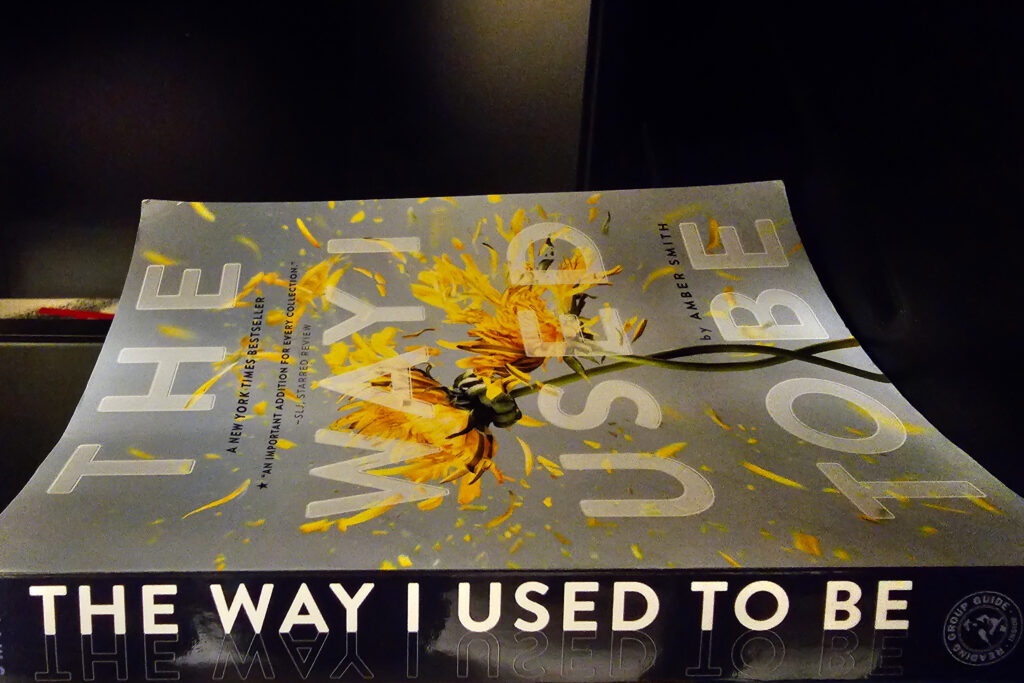

As she lay in the ICU bed yesterday, demonstrating no meaningful mental anything, and struggling to breathe, my hope deflated. That explains the Featured Image, by the way. The book lay low, but prominently, on a cart in the waiting room nearby our daughter’s regular room. I wondered about the way she used to be and what way she would become, depending on the extent of brain damage. Will she one day ask about the way I used to be? I couldn’t leave without documenting that thought, using Samsung Galaxy S23 Ultra. Vitals: f/2.2, ISO 1600, 1/125 sec, 13mm (film equivalent); 1:37 p.m. PDT, March 16.

This morning, I arrived at the hospital with low expectations, only to be surprised. The wonderfully friendly and thorough nurse bounced into the room and boisterously announced: “She talked!” The overnight nurse—when conducting the (every-four hour) neural tests of seeing how much our daughter could follow commands—elicited responses to several questions. The behavior repeated for the day shift, too.

Our daughter happened to be awake, and the nurse asked her name, which she said rather raspy, repeated with her full name. She knew where she was. “ICU”. And the month. Other developments followed: the upper lobe of her lung reinflated and she no longer needed any oxygen. Period. All that despite partial collapse to resolve. By early evening, she was in a regular room once more with lots of physical (and mental) rehabilitation ahead.

While we can’t guess the extent of recovery, there is relief: This was a pretty good day.