Steve was right, and I don’t refer to Apple cofounder Jobs, but to an iPhone buyer I met 10 years ago today. He was among the eclectic group of people waiting outside Apple Store Montgomery Mall to spend $499 or $599 on the fruit logo company’s first smartphone. The amount was outrageous at the time for a locked, unsubsidized handset. “I think this is a day that you’re going to see a change in how computers, how handheld computers are done”, he told me. “I think we’ll look back in 10 or 15 years, and like on that day the gadget came out…it changed the game”. Could anyone realistically disagree a decade later?

But you had to be a believer in June 2007, with iPhone launching on a single carrier (newly rebranded AT&T) in a single geography (USA) from a company with no cellular device experience going against hugely established competitors—with Nokia, the smartphone’s inventor, standing atop the heap. By every sensible measure imaginable, Jobs and his team took nothing but risks, making Steve the customer’s prediction all the more remarkable. (In the Featured Image, he holds a homemade countdown clock to sales start. Seven minutes to go!)

Two Themes

Backtrack: Late summer 2006, veteran journalist Walt Mossberg and I sat at lunch talking about Apple, among other techs. Rumors raged about the company developing a cell phone. I expressed misgivings. I didn’t see how Jobs could take on an established, entrenched industry and succeed—or even try. Of course, I was wrong. The CEO announced the iPhone less than a half-year later, during January 2007 Macworld.

Every few months, during the Noughties, before my family relocated from metro-Washington, DC to San Diego, Walt graciously would meet me for lunch at Mama Lucia to talk tech companies. Funny, I wouldn’t eat at the restaurant now; in July 2013, I gave up pasta, considerably cutting back carb consumption for health reasons. In the same Rockville, Md. plaza as the yummy Italian eatery was the shop where I bought my digital photographic gear—Penn Camera, which closed in 2012. The upscale mall down the road, White Flint, where my family regularly frequented, shuttered in 2015 and was later torn down. Steve Jobs is gone; he died in autumn 2011. And Walt? He is retired as of this month. But the iPhone remains—an iconic symbol of a decade that changed computing.

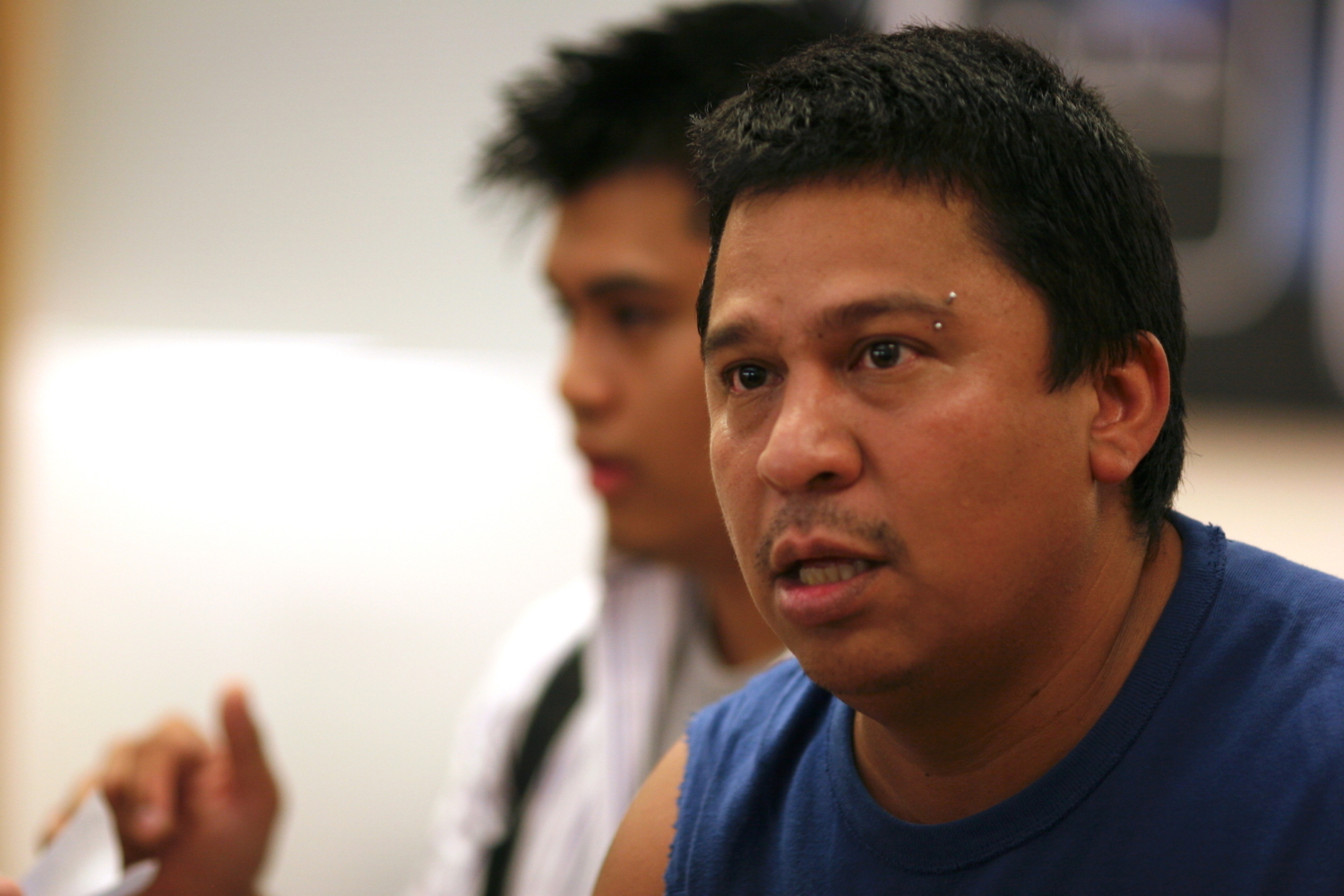

When I reflect on the device’s launch day 10 years ago, two themes stand out, as expressed in my June 30, 2007 reflection “The iPhone Moment“: “The people I talked to in line yesterday had a sense of being caught up in a historical moment”; other shoppers shared Steve’s sentiment, but he articulated it best. They “made up one motley group—representing a broad swath of America. I saw in the line people of all races, ages, and lifestyles…they shattered geek stereotypes”. I had covered plenty enough tech events and product launches to know whom to expect. But outside Apple Store waited brawny guys with tattoos and eyebrow piercings and lots of women. They foreshadowed the future of the smartphone as a tool for creativity and invention and something to be desired by everyone—not just gadget geeks.

For all the differences, the group shared something in common: Their phones, whether flip or candybar, baring naked keypads and displeasing user experiences. Everyone I interviewed wanted something more personal, more responsive, more intimate. More alive. I asked some of the line waiters to “show us your phones“. In the photo above, Steve—prognosticator of future trends—stands between the taller dudes. (For more pics, see my SmugMug gallery as posted following the launch.)

Being Part of You

Jobs’ design team delivered what these people dreamed of possessing, by using capacitive touchscreen and spatial sensors to make a cellular handset more responsive to the user. Apple’s longstanding approach to computer/device design is consistent and pervasive, and iPhone is its pinnacle: Humanization. Apple seeks to humanize complex technological products. There has been much—way, way too much—written about the company’s design ethic in context of products that look good.

Related: Improved functionality through design. But there is something more fundamental to Apple’s approach: Creating products that are easy to use by making them more an extension of the human being—making them more part of you. That’s the magic of touch, or the device anticipating the user by presenting the screen when pulled away from the face or blanking out when brought up to the ear. These attributes were core to Apple’s original iPhone success, the models that followed, and Android touchscreen imitators that spread across the planet.

By the time Apple launched the App Store in summer 2008, change was clear to me. For the now defunct Microsoft Watch blog, I asked: “Will your next PC be a smartphone?” A year later, on my personal blog, I took the affirmative: “Your Next PC is a Smartphone“—illustrating the post with Nokia N96 photo (foolishly), rather than iPhone. I had already met some sole-proprietors who ran businesses from BlackBerries or iPhones and rarely, if ever, used laptop or desktop computers.

And why not? Apple truly brought intimacy to the cellular device experience, not just utility, such that the smartphone put the P in personal computing. During holiday quarter 2010, global smartphone sales/shipments exceeded PCs for the first time, according to IDC. Sixteen percent of those 100 million handsets were iPhones.

The device carried with you everywhere, used to communicate and to socialize, to consume content and to invent, is truly personal and intimate. For many of us, our smartphone is constant companion and friend—the trend iPhone started. Sign of the changing times: During first quarter 2017, PC shipments fell below 63 million units, for the first time in a decade. That’s right, since the same year as iPhone debuted. Gartner predicts that for all 2017, smartphones will eclipse PCs—1.9 billion units to 265 million.

The Next 10 Years

Later in the year, Apple will release iOS 11, which went into public beta this week. I find it to be the most perplexing version to date. Rather than move forward, as done so brilliantly a decade ago, the company appears to go in reverse. Apple adds many, maybe too many, macOS-like features to the mobile operating system during time of the PC’s continuing decline—circumstance that the company helped create. So why, other than perhaps preserving its own status quo, should Apple bring back the past rather than make the future?

In 2017, and the years ahead, PC takes on new nomenclature: personal context. That’s the new PC era, and it doesn’t take Steve Jobs visionary thinking to see how this path unfolds. Google’s design ethic is more contextual: Provide what you want, anytime, anywhere, and on anything. Except the search and information giant mainly develops platforms and services. Apple also makes devices, from smartphones to smartwatches to tablets, that when used together with connecting cloud services can make personal context even more living, breathing, and human than the design concepts behind the original iPhone. Perhaps the future is the past, and moving ahead means looking behind at attributes from the desktop/laptop motif. I’m not convinced. You tell me.

For certain, iPhone is more intimate and expansive than first presented. When Jobs introduced the screen-slate about ten-and-a-half years ago, he pitched not one thing but three: “A widescreen iPod with touch controls. The second is a revolutionary mobile phone. And the third is a breakthrough Internet communications device…These are not three separate devices. This is one device—and we are calling it iPhone”. Fast-forward to today and the question isn’t what iPhone is but what it is not, because there are so many capabilities, whether inherent or added by apps. Need I bother to list them? You know.

Americans are iPhone addicts, and it shouldn’t surprise that the device is popular on home turf. For 2017, eMarketer projects that 43.7 percent of U.S. smartphone users will be on some model of iPhone compared to 52.2 percent for Androids. The United States is the third largest smartphone market, with 9.2 percent global share, falling behind India (11.2 percent). China is largest (26.2 percent).

Steve the customer pegged this day a decade ago, and I doubt even he could have predicted how far-reaching would be iPhone’s market disruption, whether measured directly or across technologies. For sure, Apple looks little like it did before the device launched. For example, during first calendar quarter 2007 (fiscal second), sales reached $5.26 billion, resulting in net income of $770 million. Macs accounted for 43 percent of revenues. During the same time period in 2017: $52.9 billion revenue and $11.07 billion net income. That’s right, in 10 years, revenue and income expanded by about 10 times. iPhone accounted for two-thirds of revenues. Stated differently, Apple’s profit for the last reported quarter is greater than that combined for fiscal years 2006, 2007, and 2008 ($10.32 billion). Similarly, revenue exceeds all of fiscal 2009 ($42.9 billion). The cash afterburners started firing during fiscal 2010, when annual sales reached $65.23 billion. That’s a different tenfold increase, after just three years of iPhone sales.

Looking ahead, Apple’s challenge is transcending itself—something I am skeptical the company can do by preserving dependence on its status quo. Stated differently: Actual iOS devices, excluding derivatives such as watchOS, accounted for 70 percent of Apple revenues during fiscal second quarter 2017. Lump them in, and add related cloud services, the projected number is closer to 80 percent. At the height of Windows’ dominance, Microsoft’s revenue was similarly lopsided; software stagnation and complexity creep resulted rather than self-disrupting innovation. Sometimes success is a burden.

CEO Tim Cook helms a ship that sails the iOS seas, much like Microsoft chief executive Steve Ballmer did across the Windows ocean. The question: To what destination? If you see Steve the iPhone customer, please ask him.

Editor’s Note: A version of this story appears on BetaNews.